Tax and Corporate Governance: What Tax Authorities Expect of Companies

1. Tax and Corporate Governance in the Limelight?

While tax burden is always one of the primary concerns for corporate management and finance, it is questionable whether tax has always been amongst the core factors of corporate governance. Christian Nowotny (2008) points out possible reasons for this relative low profile of tax as a corporate governance issue; tax is considered as too technical to be discussed at the board of directors, and the minutes on the discussion of tax issues at the board of directors may attract the attention of tax authorities, while corporate governance codes are primarily designed for attracting investment.[1] On the other hand, this traditional relationship betwixt tax and corporate governance has been changing, and tax is pushing forward its frontiers into what has traditionally been considered as corporate governance affairs. Many tax authorities, particularly in the advanced member economies of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), are adopting a new co-operative compliance approach, which aims to ensure tax compliance through the voluntary enhancement of internal control and corporate governance.[2]

2. Why Tax and Corporate Governance Related?

If tax authorities consider that good corporate governance and internal control are important elements of tax compliance, to what extent tax are corporate governance and internal control interlinked one another?

Corporate governance is the system by which companies are directed and controlled (Cadbury Report (1992)).[3] And the board of directors, the primary institution driving corporate governance, is responsible for systems ensuring legal compliance including that of tax laws.[4]

A chief objective of corporate governance is the integrity of financial reporting, with which listed companies are accountable to shareholders and the market. From a tax perspective, reliable financial reporting is also the basis of tax compliance; in this regard, companies are accountable to national treasuries and tax authorities as well.

The board is expected to set corporate strategies and provide leadership therefore.[5] In order to ensure high standard tax compliance, leadership and commitment on the part of management are sine qua non; for high-level tax compliance requires beefing up internal control covering the entire operations of company.

3. Co-operative Compliance Programmes

In tandem with international discussions on corporate governance and tax administration lead by the OECD, tax administrations in many of the OECD member countries are implementing a co-operative compliance programme, which typically targets large businesses.

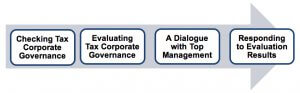

In Japan, the National Tax Agency of Japan (NTA) is carrying out a programme to enhance tax corporate governance, which was initiated as a pilot in 2011.[6] The programme aims to address the tax corporate governance of very large enterprises, numbering approximately 500 nationwide, on the occasion of tax audits. Figure 1 illustrates the process of the tax corporate governance programme on the occasion of tax audits, set out by the NTA’s administrative guidelines issued in June 2016.

At the time of a tax audit, a tax auditor evaluates the effectiveness of tax corporate governance, and then an audit executive of a regional taxation bureau holds a dialogue with the top management of company. In response to the evaluation results, for company with good tax corporate governance and of low priority for audit, the NTA will mitigate the burden of audit and extend an interval between audits for one year. Whilst the audit interval of large businesses varies, if the audit interval of company is every two years with one audit-free year, the company may have two audit-free years as a result of an audit interval extension. In return, during the audit-free years, the company is required to disclose transactions with which the tax authority is liable to disagree, such as the reporting of large extraordinary losses.

The State Agency for Tax Administration of Spain is also undertaking a co-operative initiative. The Spanish Tax Agency and a group of large businesses jointly set up a Large Business Forum in 2009, and the forum drew up a Code of Best Tax Practices in 2010. The Code of Best Tax Practices aims to improve the application of the tax system, and contains a series of recommendations for both companies and the Tax Agency.[7] As of February 2018, the code is adhered to by 136 companies.

4. What Tax Authorities Expect for Corporate Governance

Co-operative compliance programmes tend to set the strengthening of governance and internal control as a prerequisite or an objective. In this regard, what do tax authorities expect of companies?

As explained in Section 3., the Japanese NTA’s programme to enhance tax corporate governance evaluates the effectiveness of tax corporate governance at the time of an audit, and its 2016 administrative guidelines make clear five evaluation items:[8]

1) Engagement and guidance of top management,

2) Organisation and functions of accounting and audit divisions,

3) Tax and accounting procedures with internal checks and balances,

4) Dissemination of information and recurrence prevention measures, and

5) Measures to control inappropriate acts.

It may be worth noting that the programme attaches importance to the first item, i.e. engagement and guidance of top management; for the programme considers that the active engagement and guidance of top management are indispensable for the enhancement of tax compliance. Each item has more detailed evaluation points. For example, with respect to the first item, company will be asked whether company precepts, principles or compliance guidelines refer to tax compliance.

The Code of Best Tax Practices made by the Large Business Forum of Spain also emphasises the importance of the commitment of the board of directors, and recommends that the board of directors should be fully informed of tax policies applied by company.[9]

5. Conclusion

Tax authorities in many of the OECD countries have introduced a co-operative compliance programme, which aims to enhance tax compliance based upon a co-operative relationship betwixt a tax authority and taxpayers – typically large businesses. And the enhancement of corporate governance and internal control is part and parcel of these co-operative compliance programmes.

Whilst a co-operative compliance programme aims at the voluntary raise of compliance level on the part of corporate taxpayers, high standards cannot be met without working on governance and internal control. As Wolfgang Schön (2008) points out, company are not a single individual, but a nexus of contracts, and tax obligations are allocated within the organisation and legal framework of company.[10] Even though management has willingness to comply with tax rules, non-compliance could occur in business operations without the knowledge of the management and accounting division.

Co-operative compliance programmes are intended to be beneficial both for taxpayers and tax authorities. Dave Hartnett, former Permanent Secretary for Tax at HM Revenue and Customs put, for corporates who embrace corporate responsibility, we see the business as a lower risk and where the compliance track record is sound, we audit less often and then focus on bigger risks.[11] It can be said that enhanced governance and internal control are a key for a stable relationship with the tax authorities.

Whilst this article could not fully explore, it is important that governance and control cover overseas operations as a multinational enterprise, in light of the current restructuring of international taxation rules led by the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. The OECD’s 2016 report, Co-operative Tax Compliance has emphasised, as a result of BEPS, it has become even more crucial for multinational enterprises to be in control of tax risks today.[12]

[1] Christian Nowotny. 2008. Taxation, Accounting and Transparency: The Missing Trinity of Corporate Life, in W. Schön, ed., Tax and Corporate Governance, p. 101, Springer.

[2] Satoru Araki. 2017. Co-operative Tax Compliance: An Asia-Pacific Perspective, Asia-Pacific Tax Bulletin, Volume 23, No. 2, International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation.

[3] Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance. 1992. Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance, par. 2.5. The report published in London is also called the Cadbury Report as the committee was chaired by Adrian Cadbury.

[4] OECD. 2015. G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, p. 45.

[5] Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance, supra note 3.

[6] Araki, supra note 2, p. 4.

[7] Agencia Tributaria, Memoria 2016, 5.1. Foro de Grandes Empresas y Código de Buenas Prácticas Tributarias: http://www.agenciatributaria.es/AEAT.internet/Inicio/La_Agencia_Tributaria/Memorias_y_estadisticas_tributarias/Memorias/Memorias_de_la_Agencia_Tributaria/_Ayuda_Memoria_2016/5__ALIANZAS_EXTERNAS/5_1__Foro_de_Grandes_Empresas_y_Codigo_de_Buenas_Practicas_Tributarias/5_1__Foro_de_Grandes_Empresas_y_Codigo_de_Buenas_Practicas_Tributarias.html

[8] Araki, supra note 2, pp. 4-5.

[9] Foro de Grandes Empresas. Código de buenas prácticas tributarias, 1.4.

[10] Wolfgang Schön. 2008. Tax and Corporate Governance: A Legal Approach, in W. Schön, ed., Tax and Corporate Governance, pp. 32-34, Springer. Schön (2008) doubt if the directors of company individually owe obligations towards the tax authorities, though.

[11] Dave Hartnett, The Link between Taxation and Corporate Governance, in W. Schön, ed., Tax and Corporate Governance, p. 6, Springer.

[12] OECD. 2016. Co-operative Tax Compliance: Building Better Tax Control Frameworks, p. 12.

9,109 total views, 9 views today

1 comment

I appreciated it when you shared that corporate governance codes are essentially designed to attract investment. In this way, the company will be able to find investors who are interested in the business. I would like to think if a company needs to improve its corporate governance, it should cosdneir working with a reliable consulting company.