Carbon taxation in developing countries – United Nations Workshop (First session)

Climate change mitigation is a global emergency. The world faces already graves consequences of lack of previous collective action, and the increase in climate-related damages shows the consequences of the too slow global answer to the threat of carbon emissions on the warming of our planet’s atmosphere.

As you may know, the world has answered to the growing awareness of this threat with several global agreements, the first one being the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1992) and last one being the 2015 Paris Agreement, almost universally ratified, where all countries have commit to NDC (Nationally Determined Contributions) to reduce their carbon emissions and slow down the warming of the earth’s climate.

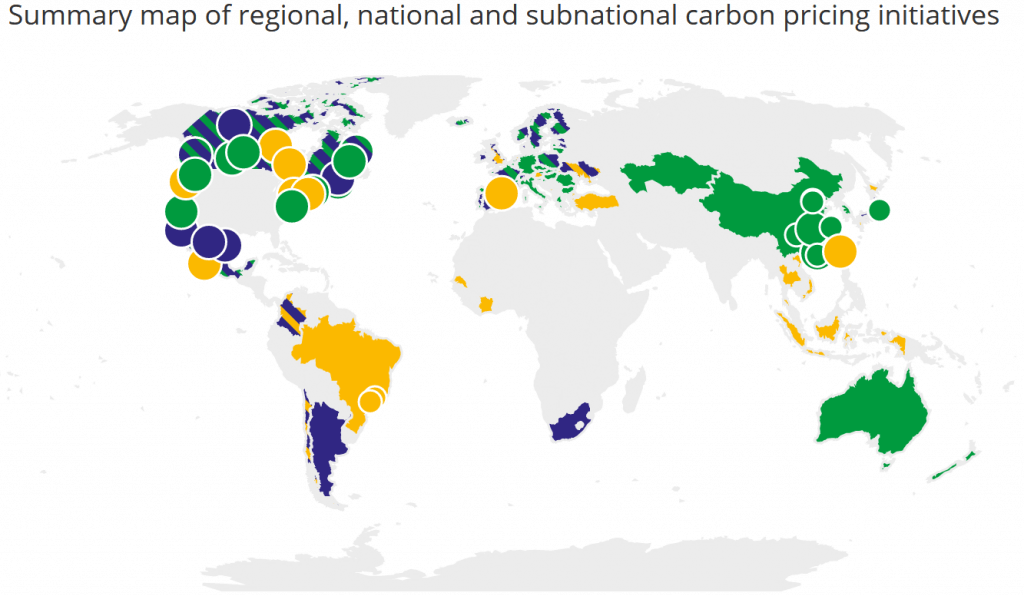

Among the main Public policies aimed at mitigating the threat are ETS (Emission Trading Schemes) and CT (Carbon Taxes). Both instruments keep growing: In 2020, 31 national or sub-national jurisdictions have adopted ETS and 30 have adopted Carbon taxes. At this time, these regulations cover only 20% of global carbon emissions, and only 5% are at a price level deemed sufficient to meet the goal of preventing a global warming above the fateful mark of 1.5° of temperature expressed in the Paris Agreement. In 2020, this price is considered as evolving around $30 per ton of CO2 emitted.

In the UN webinar, we learn from the Coordinator, Ms. Natalia Aristizabal, that the good news is that no less than 62 new instruments are in process of elaboration, or under consideration. The workshop focused on the aspects described in chapter 3 of the Manual of the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation, “Designing a Carbon Tax – Manual of Carbon Taxation”. [1]

The mapping of the implementation of carbon taxation instruments illustrates the diversity of approaches: Some countries, such as Canada, have both systems operating in their various states, with a federal system applying only to states that do not implement their own system. Others, such as the United States, have instruments implemented in some states, such as California’s ETS, but not at the federal level. In the European Union, national approaches are coordinated at the regional level.

Current map of carbon pricing instruments[2]

Green: ETS implemented or scheduled

Yellow: Considered an ETS or carbon tax

Blue: Carbon tax implemented or scheduled

Green/Yellow: ETS implemented, carbon tax under consideration

Blue/yellow: Carbon tax implemented or scheduled, ETS considered

ETS and Carbon taxes

An important difference between ETS and Carbon taxes is that ETS are basically “command and control” instruments: they set a limit of emissions for which prices have to be paid, even if they organize markets for the sales or purchase of these allowances and the prices fluctuate according to the proximity of the “ceiling”.

Carbon taxes, on the other hand are “market based” instruments: They set a fixed price per ton of emissions, and let the taxpayers decide how to handle their emissions, as long as they pay for them.

The two approaches to carbon taxes

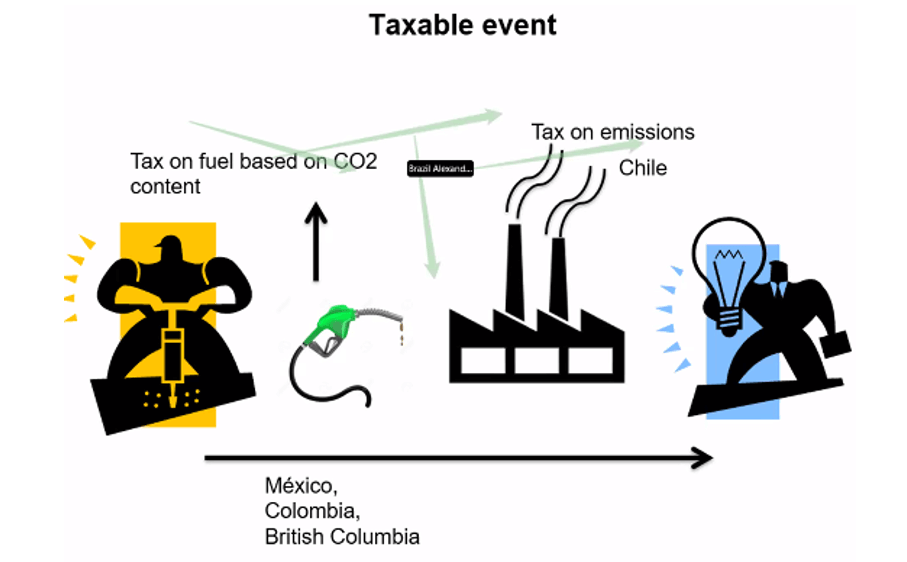

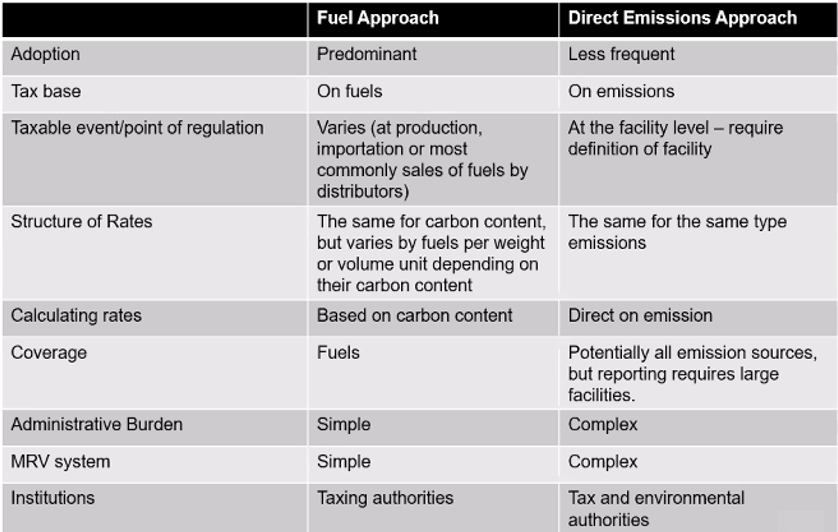

The Chapter 3 of the UN manual on carbon taxation presents in details the two models, two approaches of carbon taxes adopted by countries: One is based on taxing the fuels, and the other is based on taxing the carbon emissions.

These two approaches differ in defining the taxable event

Source: UN Subcommittee on Environmental Taxation

The first approach, fuel-based carbon taxation, is implemented by the European Union, Mexico, British Colombia and Canada, is the most widely adopted so far, with the highest tax rate being implemented in Sweden (USD 126/metric ton of CO2). For an implementation of this tax, this system has the advantage of easily using the existing monitoring system for the excise taxes on fossil fuels traditionally implemented in most countries. The tax administrations , or in some countries the Customs administrations (where fuel is fully imported), are already used to controlling the importation and transfers of fuels, and the technical aspects of implementing these taxes are not considered a difficult issue. In the European Union, the taxpayers are the recognized companies distributing the fossil fuels, and the tax is charged once a determined amount of fuel leaves the official storage spaces to enter the distribution chains. This limit the number of taxpayers that the TAs have to monitor.

The second approach, a tax on direct carbon emissions, is implemented by Chile. In this system, the amount of carbon emissions produced by powerful generators (mainly for power generation) are measured and the tax is calculated based on these emissions.

This approach requires a system of Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) which, in turn requires collaboration between the tax authorities in charge of collecting the tax and the environment authorities that set the criteria and have the expertise for the monitoring and technical verification. This is an innovative approach, which covers only the emissions of the big emitters of CO2. In Chile, about 40 % of the emissions are covered by this measurement system.

In both cases, the systems are progressively adjusted, in terms of identifying the taxpayers and adjusting the tax rates. The carbon taxation is in both cases, in continuous improvement and in most cases the tax rates are progressively increased

If your country has less emissions from fuel combustion and more emissions from other sources, such as change in the use of soils, it is interesting to consider alternatives to the fuel approach. Countries where the emissions are not essentially resulting from the burning of fossil fuels may consider useful developing the taxation of direct emissions, although it implies a heavier administrative burden.

Source: Mrs. Susanne Akerfeld, UN Subcommittee on Environmental Taxation Issues.

The workshop concluded with a recapitulation:

Important choices when designing a carbon tax

We will keep summarizing this essential work of the UN subcommittee on environmental taxation.

[1] Mandatory reading: UN Carbon Taxation Handbool: See https://www.un.org/development/desa/financing/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.financing/files/2020-05/CRP18%20chapter%204%20clean%20version_21-04-2020.pdf

[2]Source: World Bank, Carbon Pricing Dashboard, November 2020 https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/

15,911 total views, 1 views today