The Financial Transaction Tax (ITF) in LAC countries

Heterodox taxes

During the nineties, the doctrine of the “Chicago boys” and economic orthodoxy were on the rise, and any tax that did not follow the classical tradition, that is, that was not a tax on income and wealth (direct taxation) or a general consumption tax -VAT- or other specific (indirect taxation), was cursed and its implementation considered heresy.

It was curious to me that they did not even bother to study their “harmful consequences” and were simply demonized with the withering definition of “distortive”, as if the rest of the taxes were not. My degree of astonishment reached the maximum when in an international meeting, a tax expert from an international organization described them as “banana growers”, as if there was no need to mention them.

This motivated me to study them, to know their causes, characteristics, categories, objectives, and consequences. Hence, in 2009 within the framework of ECLAC (United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) I presented my paper on the subject and designated them as “heterodox taxes”, that is, opposed to orthodox or classical[1].

To understand this policy, it must be considered that it has multiple causes, instrumentation, and objectives. At that time, the concern of the tax policy makers was to increase revenues, in the face of a traditional tax system incompetent to do so for reasons of the tax structure (high tax expenditure), weakness of the tax administration, economic instability (economic crisis, high informality) and fiscal sociology (low level of consciousness or discipline).

This type of tax policy covers, from taxes on financial transactions (both in national currency and foreign currency), business taxes (assets, presumed income, “minimum tax”, etc.), taxes on the primary activity of the economy (presumptions on the income of the agricultural sector, withholding on exports, etc.) and taxes on assets (on large fortunes). A debate remains to be resolved on whether simplified regimes for small taxpayers are “heterodox” or are part of “orthodoxy” as a threshold or bridge towards it.

The Financial Transaction Tax (ITF)

It corresponds to differentiate this tax from the so-called “Tobin tax”[2] which at first was a tax intended to tax the operations of conversion between currencies produced in cash, and currently it is a tax on all transactions of stocks, bonds and currencies called “Financial Transactions Tax” (FTT).

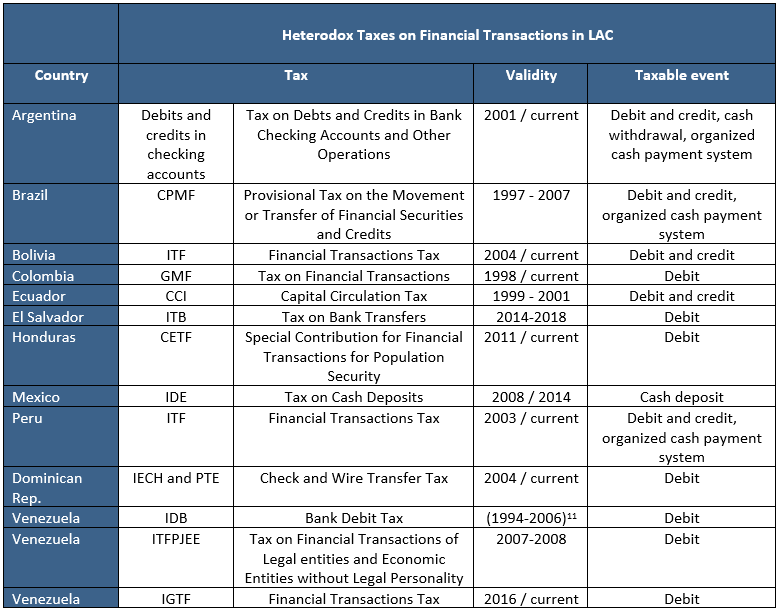

In this post, I will limit myself to developing heterodox taxes on financial transactions in the region, intended to tax operations carried out by taxpayers within the financial system.

Argentina (1983)[3] was the forerunner of this tax (it only taxed bank debits and was called by the doctrine as a “tax on checks”), which was later extended to other countries in the region. It generated significant resources with almost no costs for the tax administration and reached the movements of almost all taxpayers (including informal ones and those exempt or exonerated from orthodox taxes).

Brazil (1997) [4] with the CPMF (Provisional Contribution of Financial Movements) was the precursor to extend it also to financial credits[5]. In 2001 Argentina applied it with the “Tax on debits and credits in current accounts and other operating accounts.”

The characteristics of the heterodox taxes on financial transactions were the following:

In the region, among other countries, these applied it:

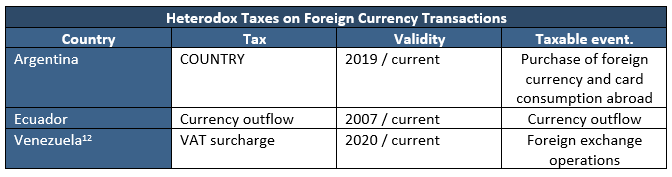

Tax on Foreign Currency Transactions (ITD)

With respect to this taxation, its objectives were:

In the region it is applied by:

Conclusions:

[1]“The Heterodox Tax Policy in Latin American Countries“, (2009) CEPAL, Santiago.

[2]It owes its name to the American economist James Tobin, Nobel Laureate in Economics in 1981. This tax would be paid by members of the financial sector (not consumers), to control the stability of a country’s currency.

[3] Ley N° 22.947 del 14/10/1983.

[4]It was not extended in 2008 when it raised the equivalent of $ 22 billion.

[5]The name of Tax on Financial Transactions (ITF) is more appropriate from a technical point of view and has already been adopted by Bolivia, Peru, and Venezuela.

[6]While some countries complied with the transitory status, others were extending it or replacing it with another similar tax.

[7]In Ecuador, it collected 3.5% of GDP in 1999.

[8]In some cases, it was to replace the Income Tax (Ecuador) or obtain financial information to control said tax (Peru).

[9]Withholding and perception at source in the financial system.

[10]Variable by country.

[11]Various derogations and reimplantation.

[12]A differential tax on currencies was announced within the Tax on Large Financial Transactions.

[13]Orthodox critics at the outset argued that it would cause “unbanking” and would force the rate to rise year after year to maintain collection, which would lead to further unbanking. None of it happened. This country maintained the same rate 20 years ago and the collection was increasing until today it becomes the third tax in collection of the system.

[14]In Argentina, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation has ruled on 12/12/2017 on the constitutionality of the regulatory framework of the Tax on Bank Credits and Debits, putting an end to a controversy of several years. In the case “Piantoni Hnos. SACIFI and A.” and “Máxima Energía SRL” resolved that said regulatory framework is constitutionally valid resulting, consequently, being reached by the tax on the increased rate provided by law, the amounts in cash that are usually deposited in the bank account of a supplier.

[15]Very low in Bolivia and Peru.

[16]For example, Brazil, where it went to the health sector.

8,789 total views, 41 views today