New Financial Secrecy Index publication indicates Latin America should strengthen certain aspects of administrative assistance in tax matters (Part 1)

Introduction

In June 2025, the Tax Justice Network presented the most recent update to one of its flagship publications, the Financial Secrecy Index (FSI). The FSI is based on a legal assessment of the laws and regulations of 141 jurisdictions, including 36 countries from the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region[1]. Based on the assessment, countries obtain a ‘secrecy score’. A country’s secrecy score is weighted in function of its global share of exports of financial services to produce its ‘FSI score’. The FSI score, in turn, reflects each country’s contribution to the global financial secrecy and determines a country’s ranking on the Index. The 2025 FSI ranking can be found here.

The FSI is updated on a rolling basis, meaning that instead of a single, whole-index update, subsets of indicators and datapoints are refreshed over multiple update moments. The current update focuses on indicators on ‘international standards and cooperation’, and includes indicators on Public Statistics, Automatic Exchange of Information, Exchange of Information upon Request and International Legal Cooperation. The indicator on Country-by-Country reporting was also updated, in line with previous updates to the Corporate Tax Haven Index.

In this series of two blogs, we give an overview of some of our findings in relation to countries’ various commitments to administrative assistance under the (amended) multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (MAAC).

For most countries, including LAC ones, the MAAC is the bedrock of global administrative assistance in tax and exchange of information. The MAAC is the broadest existing framework for exchange of information on income tax. However, our research shows that for other aspects of administrative assistance, like assistance in the collection of foreign tax debts or exchange of information beyond income tax, the bedrock comes with serious fault lines. Through opt-outs and reservations under the MAAC, countries have the possibility to dramatically reduce their commitment to global administrative assistance.

In this series, we present some of our findings in this regard, with focus on the LAC countries. We also draw some conclusions on where this brings LAC region countries in discussions on universal and inclusive administrative assistance in the context of the upcoming negotiations of a United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation (UNFCITC).

The Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (MAAC): bedrock of exchange of information, also in the LAC region.

150 jurisdictions are currently party to the MAAC, including nearly all countries in the LAC region. One of the main accomplishments of the MAAC is that it provides acceding countries with the possibility to engage in exchange of information with all other parties to the Convention, making bilateral instruments redundant.

For example, article 6 of the MAAC, which covers automatic exchange of information, is the legal underpinning for the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for the automatic exchange of information on financial accounts. According to the latest edition of the Global Forum’s Latin American Tax Transparency report, Latin American countries are said to be receiving data on more than 4 million financial accounts in 2024 under CRS, reaching almost a trillion dollars in assets held abroad by their tax residents. It is furthermore estimated that between 2009 and 2024, the participation by Latin American countries in information exchange under the MAAC has yielded additional tax revenues of USD 28.4 billion, with 80% of that revenue linked to the CRS and voluntary disclosure programs. Automatic exchange of information is expected to generate additional tax revenue in the future when the exchange of other types of information like on crypto assets under the CARF or income from digital platforms starts taking effect. These instruments, too, are underpinned by the MAAC.

The MAAC also has flaws, and most notably a disproportionate reciprocity requirement, which often bars the participation of developing and low-income countries. Due to their relatively small financial sectors, these countries play a limited role in the provision of financial secrecy but are still required to meet the same standards as some of the most important offshore centers of the world.

One additional failing is the MAAC’s strict restriction of exchanged information to the enforcement and collection of tax. Tax evasion and other crimes like corruption or money laundering frequently go hand in hand. To allow tax information to serve the fight against money laundering, countries of the LAC region have in 2018 issued the Punta Del Este Declaration. In the Declaration, countries express their commitment for the wider use of exchanged tax information as permitted under the MAAC. To achieve the objectives of the Punta del Este Declaration, the Latin America Initiative has recently set up a pilot project for the wider use of tax information, attesting to the region’s willingness to pioneer new standards of international cooperation.

With regard to certain other flaws of the MAAC, the LAC region’s performance is less spectacular. In this blog series, we show two aspects of administrative assistance under the MAAC which deserve more attention, particularly by the LAC countries. These aspects are assistance in the collection of foreign tax debts and exchange of information beyond income tax.

Administrative Assistance in the collection of foreign tax debts

As our world becomes ever more interconnected, and individuals and companies spread their activities in different countries, tax authorities (including all CIAT members) will require additional instruments to enforce tax laws, even if this involves seizing foreign assets of a taxpayer who is abroad and not willing to pay the tax they are owed.

Increasingly so, tax authorities will have to rely on assistance in the collection of foreign tax debts by other countries.

Article 11 of the MAAC provides a multilateral legal ground for collection assistance. This means that each of the 150 parties to the MAAC can potentially rely on each other to help executing tax debts that are final and enforceable in case the taxpayer has only foreign assets.

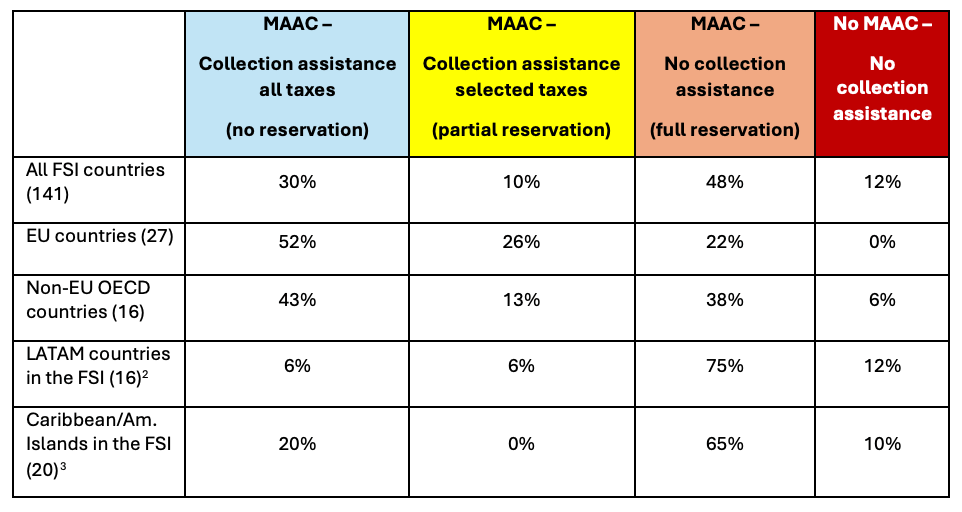

A lesser-known fact is that the MAAC allows countries to opt-out of giving any collecting assistance under the Treaty. Our analysis of the country reservations made under the relevant provision (article 30(1)(b) from the MAAC) shows that a large number of MAAC countries have actively limited its commitment to collection assistance as much as possible. This also includes most countries in the LAC region.

The frequent use of this reservation is problematic, as it completely erodes the MAAC’s capacity to provide a multilateral regime for administrative assistance. For this reason, LAC countries do not score well on this part of multilateral administrative assistance.

In theory, countries can also rely on bilateral tax treaties for a legal ground for collection assistance. In practice, very few bilateral tax treaties include the provision of article 27 of the OECD/UN Model. Mexico and Colombia are examples of countries with collection assistance provisions in a few of their bilateral tax treaties. In recent years, Ecuador and Peru have for the first time been doing the same in a few new tax treaties.

While these are laudable developments, bilateral tax treaties can be problematic instruments to regulate administrative assistance. In certain bilateral relationships, countries may believe tax treaties would be too costly (because they restrict source state taxing rights) or simply not obtainable (because the prospective treaty partner is not interested). Collection assistance should therefore not be made dependent on the existence of a bilateral tax treaty. It should be granted on a multilateral basis and in relation to all assistance requests by all countries that meet the requirements for assistance.

Many other LAC countries, including Brazil and Argentina, have opted out of collection assistance in the MAAC and have also not included collection assistance provisions in any of their bilateral tax treaties. This principled stance in the region against collection assistance is probably a remnant of the so-called ‘revenue rule’, the long-standing principle according to which courts and tax authorities of a country will, as a principle, not enforce the tax laws of another country.

We believe this policy is at odds with the LAC region’s pioneer role in other aspects of administrative assistance. It is also outdated in this ever more globalized and digitalized world where taxpayers, their income and their assets are highly mobile. For example, for countries to enforce and collect digital services taxes or significant economic presence taxes on non-resident companies with no physical presence in the country, collection assistance is key if the foreign taxpayers fail to pay the tax that is final and enforceable. In the massive cum-ex dividend stripping scandal, countries’ ability to reclaim unduly paid tax refunds to non-resident investors ultimately depended on the availability of a legal ground to compel collection assistance.

LAC countries need to reconsider their objection to collection assistance. Like the countries of the European Union (via Directive 2011/44/EU) or countries in Africa (via the ATAF African Tax Administration Forum Agreement on Mutual Assistance In Tax Matters (AMATM)), LAC countries could make collection assistance to other countries in the region compulsory through a regional agreement.

It would be more efficient for LAC countries to jointly push for a truly global commitment to collection assistance. A regional commitment by LAC countries can only achieve so much, as in many instances taxpayer offshore assets will be located in other parts of the world, including the northern hemisphere. As our research shows, while EU countries and OECD countries may perform well in providing collection assistance on a regional level, many of those countries fail to extend this commitment to the Global South, including to the LAC countries.

Both at the OECD’s Forum on Tax Administration (FTA) as well as in the context of the UNFCITC Terms of Reference negotiations, countries have raised the problem of reservations under the MAAC and the resulting lack of global commitment to assistance collection. In their written submissions in the context of the UNFCITC, the G24 and countries like Mexico and Kenya urged countries to agree on a more principled and universal approach to assistance in foreign tax debts. The LAC countries should embrace and amplify this call in the upcoming UNFCITC negotiations.

_____

[1] These are 16 countries from the Latin American region, and 20 Caribbean or American Islands.

[2] Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

[3] Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Curacao, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Puerto Rico, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands and US Virgin Islands.

5,665 total views, 30 views today