Tax system: integrated or disintegrated?

Perhaps for the Latin American reader of tax matters the terms integrated and disintegrated referring to the tax system may seem unknown. Specifically, what is referred to is a topic that has been constantly debated within the theory of Public Finance: the taxation of dividends. In particular, the discussion focuses on the type of tax regime or structure on the income of companies and their owners, partners, or shareholders, to be used. On the one hand, there are proponents of a dis-integrated tax system (also called the classical system) consisting basically of two independent taxes;

On the other hand, there are positions in favor of an integrated tax regime or system (also called imputation system) in the PIT for the taxation of companies, legal entities, enterprises or corporations. However, both positions have their nuances and intermediate variants.

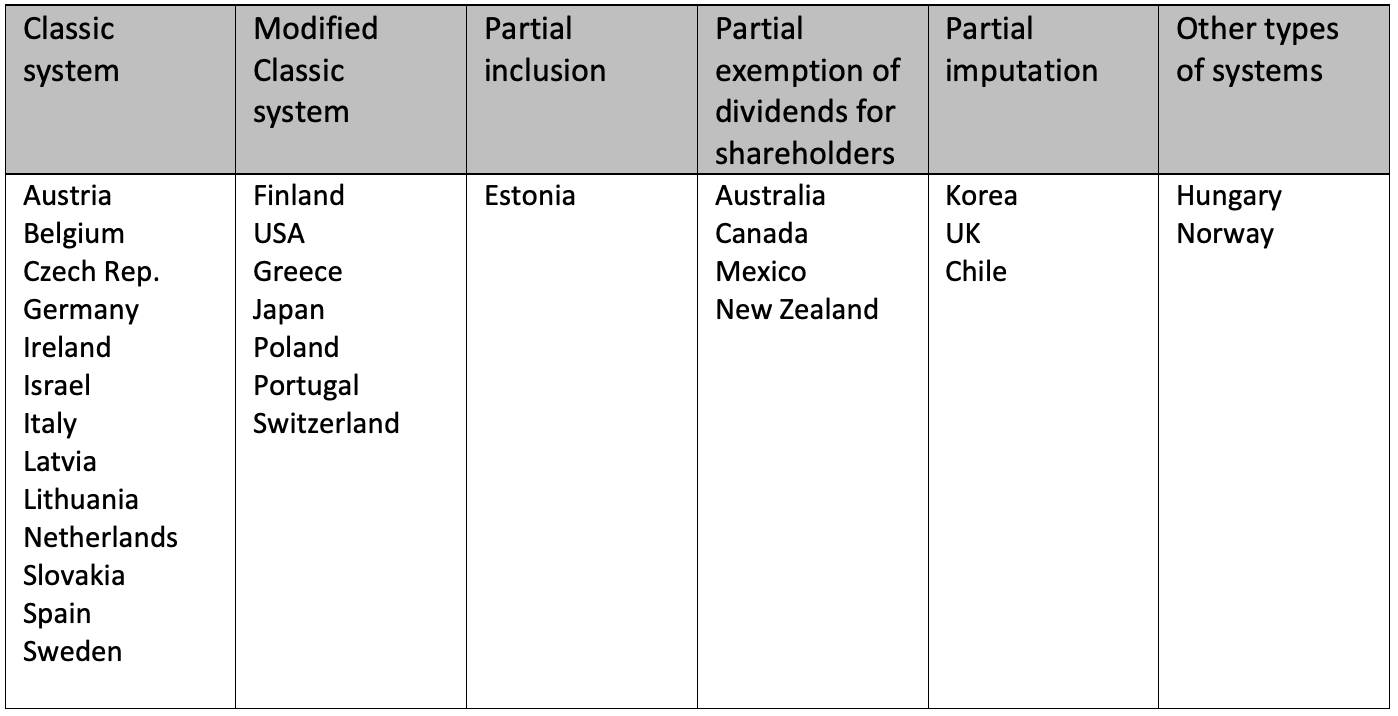

Within the OECD, the systems used have been defined as follows:[1]

Classic system: dividend income is taxed at the shareholder level in the same way as other types of capital income, for example, interest income.

Modified classic system: dividend income is taxed at preferential rates, for example, compared to interest income, at the shareholder level.

Full imputation: a tax credit is given to shareholder-level dividends for the underlying corporate income tax.

Partial imputation: a shareholder-level dividend tax credit is granted for part of the underlying corporate income tax.

Partial inclusion: a portion of the dividends received are included as taxable income at the shareholder level.

Split rate system: distributed dividends are taxed at higher rates than retained earnings at the corporate level.

No dividend tax for shareholders: no tax other than the corporate income tax.

Corporate deduction: deduction at the corporate level, in whole or in part, with respect to the dividend paid.

Other types of systems

Within this scope, the debate has been aimed at questioning the presence within dividends of a double taxation that would be generated by taxing the same source of income on two different subjects, first the company and then its owners. However, this double taxation only makes sense if we look at it from a purely economic point of view that understands that the same economic amount is taxed twice, first in the legal entity and then in the individual, which leads us to understand that the corporate form would not be more than a “shell” that hosts its owners, partners or shareholders. But if one visualizes this relationship between both taxes, first, from the legal point of view, there is no such alleged double taxation, since the flow of money comes from two legally different entities and with their own obligations and inherent in their legal conformation; on the one hand the company, and on the other hand, the shareholders. In addition, we are facing two different incomes, one is for business profits and another is for the returns of that capital (profits and dividends). Secondly, if we look at the corporate tax from the perspective of the principle of profit, then how do we explain that the limited liability of the corporate form of organization that allows the assets of the owners, partners or shareholders to be separated from the assets of the company? Is it not the state itself that recognizes this legal form and grants it the “benefit” of the advantages of the separation of these assets that justifies the corporate tax? Isn’t the corporate form the most widely used in today’s business world? Will we understand large transnational corporations as mere companies that are only made up of shareholders who receive profits from them? Or is the complexity of large holdings and chains of companies not a sign that we are not in the presence of only individual people behind companies?

It cannot be ignored that the company, in its most representative form; large transnational corporations and other legal entities, acquire rights and obligations other than those of their shareholders, which justifies their taxation.

If we take as reference the OECD member countries, we will see that the classical system is predominant in the OECD with 15 of 36 countries that use it; the disintegrated system is predominant with 26 of 36 countries that use it; and only 8 of 36 countries use an integrated system of total or partial imputation, as shown in the table below:

Classification of countries according to tax systems for the treatment of corporate and personal income in the OECD.

Source: own elaboration based on OECD. Stat, 2020

Source: own elaboration based on OECD. Stat, 2020

The experience, compared with the OECD, shows us that the disintegrated tax system is the most widely applied in these countries.

In Latin America, this discussion is especially important for Chile, which had a fully integrated system (full imputation) from 1984 to 2014, that is, 30 years with this system, to transition with the tax reform of 2014 to a semi integrated system (partial imputation).

In 2018, with a new government, the tax issue again came to the forefront and the project that the current government proposed had as its central axis the reintegration of the tax system, coming to be cataloged as “the heart” of the proposed tax reform.[2] This reflects the level of relevance this discussion has for Chile.

It is noteworthy that with regard to the discussion on the tax on the so-called “super rich” (wealth tax), most of the analysis of experts in the field has taken as a reference the OECD to point out that only 3 of 36 countries maintain a tax of such characteristics, which would make it foresee that its implementation would be a mistake. However, in defending the reintegration of the system, it is not taken as a reference that only 8 out of 36 countries maintain such a system.

Clearly, a political disjunctive is also presented here, which is related to the conception and the role of the state in a society. The European countries more than the Anglo-Saxons have a much more guarantor perception of a state that provides public services to the general population and does so with a medium-high standard. In Latin American countries such as Chile, the perception is the opposite, and that is why it is so difficult to trust that the state, as it is conceived and with the current rules, is an agent promoting better conditions of existence for the general population.

In this sense, establishing a tax system, whatever it may be, can be hasty if Latin American countries do not reach a minimum civilizational consensus. After the so-called ”social explosion ” of October 18, 2019, a space was opened in Chile to discuss a new social pact. This instance can be a great opportunity to reflect on what kind of country and society we want to build, and what role the tax system and tax policy will play in achieving these objectives. The countries of the region will be following the Chilean process and will be able to draw lessons that will allow progressing in the construction of more egalitarian societies, where the tax system is conceived as a tool at the service of the social welfare.

[1] See https://stats.oecd.org / Table II.4. Overall statutory tax rates on dividend income

[2] See: https://www.latercera.com/pulso/noticia/reforma-tributaria-horas-clave-votar-la-reintegracion-corazon-del-proyecto-del-gobierno/768434/

9,834 total views, 2 views today

1 comment

Very delighted to come across this useful article. Corporate tax rates differ greatly by country, with certain countries being regarded as tax havens due to their low rates. Because different deductions, government subsidies and tax loopholes can reduce corporate taxes, the effective corporate tax rate or the rate a corporation actually pays, is usually lower than the stationary rate, or the rate a corporation actually pays before any deductions.