A good pairing in the digital economy – Part I

PROPOSALS OF THE UN COMMITTEE AND PILLARS 1 AND 2 OF THE OECD

In gastronomic terms, a good pairing is the art of combining a certain dish of food with a certain wine, which enhances both flavors and of optimal taste results. That is, the perfect combination of wine and cuisine.

At the tax level, international organizations such as the OECD and the UN have made their own tax proposals to achieve an international consensus on the income tax on digital goods and services. Would it be possible to combine the two methods in a way that enhances both modalities and offers an optimal tax result in a globalized world? Could a harmonious conjunction further minimize those tax loopholes that some multinational companies are exploiting to erode tax bases?

Based on the current summary of both proposals and a practical example, we will try to reach the factors that could act complementarily, considering the magnitude of the taxpayer, its physical presence in the jurisdiction and the ability of a Tax Administration to exercise its monitoring role in this broad and changing universe that the digital economy proposes.

THE OECD PROPOSAL

The first of the 2013 BEPS project actions aims to design a roadmap to address the tax challenges posed by the digital economy, in response to the concern expressed in various quarters about harmful tax planning, highlighting the central problem that is the correct attribution of taxing rights between jurisdictions

After receiving the mandate of the G20 Ministers of Economy and Finance, the Inclusive Framework, through its Working Group on Digital Economy, formulated a series of reports and proposals[1] [2] [3], which lay the foundations for a principle of agreement, around a novel but complex mechanism of distribution of tax powers.

The two-pillar objective is to ensure that multinationals that are particularly consumer-oriented or have a strong digital component pay their taxes in the place where they conduct their business in a sustained and meaningful manner, whether or not they have a physical presence in the place.

PILLAR 1. Unified approach of the OECD Secretariat

Following a public consultation[4] that offered to contribute to the project, and a work program that was endorsed in Japan in June 2019 by the G20 Ministers of Economy and Finance[5], the Secretariat has developed a Unified Approach that brings together the common elements of the first pillar proposals.

The substantive aspects of this unified approach are summarized below:

In such cases, an additional profitability, Amount C, would have to be paid when it is based on the application of the arm’s length principle. In such a case, this amount should interact with Amount A so as not to duplicate the tax burden.

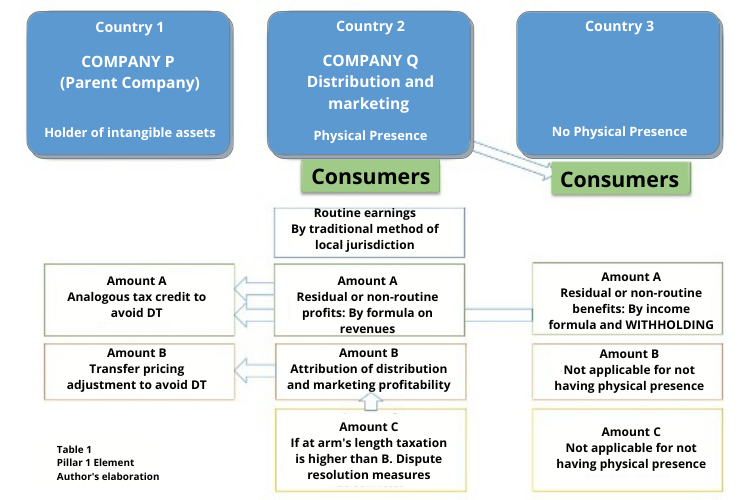

Let us look at it with an example, using Table 1[6] elaborated from the examples proposed by the Secretariat:

It is a multinational group (MNE) dedicated to offering video streaming services. Company P with seat in Country 1 is the parent company, holder of the intangibles. Company Q is located in Country 2 and is dedicated to distributing and marketing the services. In addition, it sells to end consumers in Country 3, where it has no physical presence. Both in the group and in countries 2 and 3, the income thresholds are exceeded, so the “nexus” of subjection is configured.

Country 2 retains the power to apply the tax on the routine income according to the traditional method of its local jurisdiction, for the activities carried out in it.

In addition, Amount A will tax the residual profits that company Q pays to company P through the application of a formula on sales previously determined from the consolidated EECC of the group. Company P will take this amount as a similar tax credit paid in Country 2.

Amount B shall consist of a fixed return corresponding to the marketing and distribution activities. The elimination of double taxation would be achieved through a transfer pricing adjustment between the two related parties.

Amount C would apply if Country 2 considers that the profitability allocation of Amount B results in default. To do this, it must have robust measures for the resolution of these conflicts.

Country 3 does not have a company with a physical presence on its borders, so in principle, routine activities would not be subject to taxation in accordance with this approach. However, since the minimum income amount (nexus) is exceeded, it is entitled to tax Amount A and apply a rate by way of eventual withholding.

Since there are no marketing and distribution activities, amounts B and C are not applicable in Country 3.

As can be seen in the graph, in Country 3, routine activities or local profits without physical presence are not contemplated for the taxation in this model.

In part II of the blog, we will analyze Pillar 2 and the UN proposal, with the aim of eventually complementing the proposals of both international organizations.

[1]OECD (2015), Addressing the Fiscal Challenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 – Final Report 2015, OECD and G-20 Project on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[2]OECD (2018), Tax Challenges Derived from Digitalization – Interim Report 2018, Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD and G-20 Project on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[3]Addressing the tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy – Policy statement, adopted by the Inclusive Framework on BEPS on 23 January 2019, OECD 2019, accessible at www.oecd.org/tax/beps/policy-note-beps-inclusive-framework-addressing-tax-challenges-digitalisation.pdf

[4]Public consultation document, Addressing the tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy, February 13 – March 6, 2019.

[5]OECD (2019), Work programme to develop a consensual solution to the fiscal challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy, OECD and G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD, Paris.

[6]Published at http://www.economicas.uba.ar/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/TENDENCIAS-INTERNACIONALES-EN-LA-IMPOSICION-A-LA-ECONOMIA-DIGITAL.pdf

2,595 total views, 1 views today

1 comment

Existen muchas razones para especializarse en economía y finanzas, siendo una de ellas el poder conocer en profundidad términos complejos que, aunque muchas veces la mayoría de la gente desconoce, tienen una gran importancia a nivel individual y social. Es lo que ocurre con la economía financiera, un término que hoy vamos a abordar más en profundidad.