Carbon prices in the European Union reach a record after COP26

In a previous blog article, I described the probable expansion of the taxation of carbon emissions, as a consequence of the climate emergency we are experiencing: It is predictable and ineluctable, for the survival of humanity, that the value of non-polluting activities is growing and that the economic value of polluting activities is decreasing. Delaying changes contributes to making them more expensive and chaotic in the future.

In this regard, despite delays in the decisions of COP 26 in Glasgow, carbon prices in the EU have more than doubled the level of early 2021 after the UN climate conference, as they are accepted as tool for decarbonization.

CO2 prices in the EU reached a record 66 euros/tonne on November 15, the first day of trading after the UN Climate Change Conference and amid the rise in fuel prices driven by the resurgence of gas supply fears.[1]The carbon benchmark hit a fresh record of 90.75 euros on Wednesday, December 8 (Reuters).

Carbon emission permits in the EU increased by more than 5% and more than double their level at the beginning of the year after the conclusion of the COP26 climate summit .

Carbon markets are a key tool for decarbonization and help countries “cut down” carbon. Europe’s carbon emission permits have reached a record high following the conclusion of the two-week UN COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, in which 197 attending countries agreed to reduce the use of fossil fuels.[2]

These record numbers come just after COP26 finally set the standards for a global carbon market, making polluting countries and companies pay for carbon emission permits and allowing them to trade in emissions offset credits. Carbon markets are critical to reducing carbon emissions in Europe and fostering new investments in clean and green technologies such as carbon capture and storage and green hydrogen in developing countries. [3]

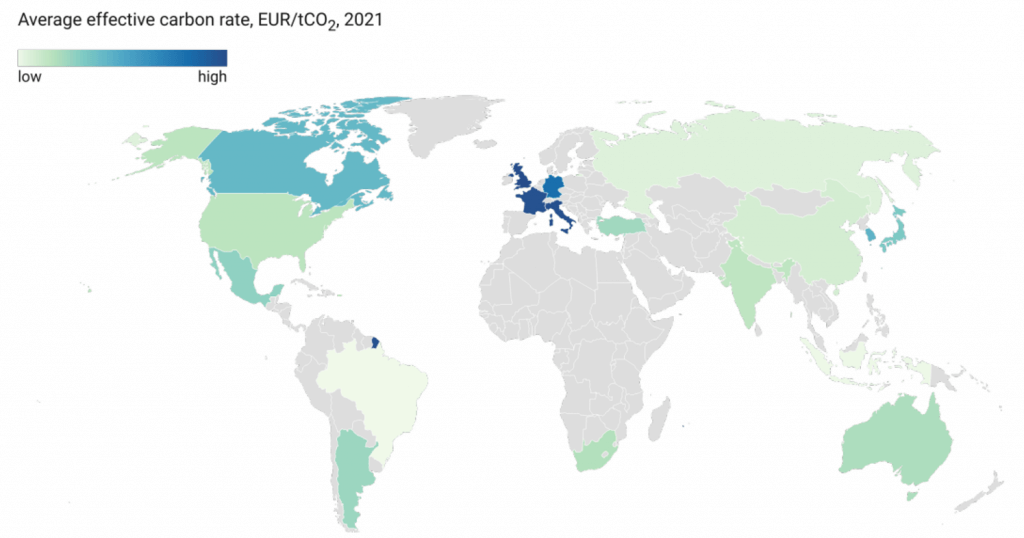

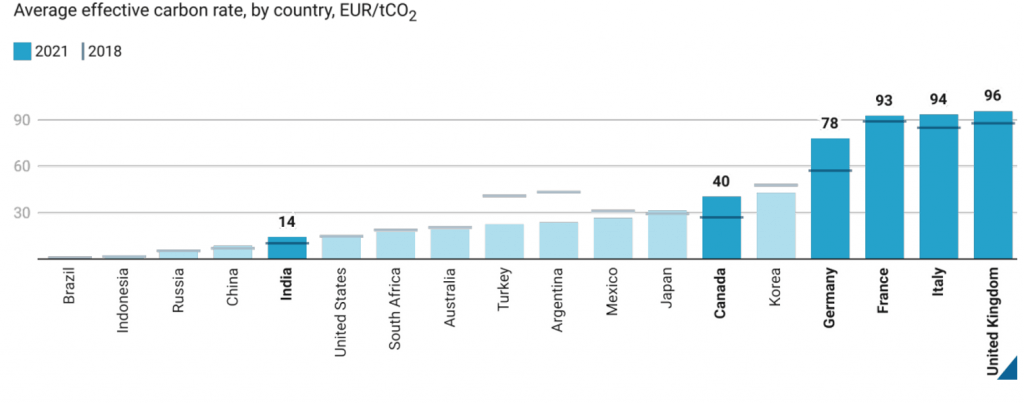

Carbon Price Inequality Raises Competitiveness and “Carbon Leakage” Concerns[4]

Discrepancy among G-20 members on the price of carbon:

The adoption of the Glasgow Climate Pact[5] at the end of COP26 will see bilateral agreements take place in a market supervised by the UN. The EU also plans to expand the bloc’s trading system to more sectors, as well as launch its ambitious carbon border adjustment mechanism[6], a tax on carbon emissions attributed to imported goods that have not been taxed. on carbon at source.

The adoption of the Glasgow Climate Pact[5] at the end of COP26 will see bilateral agreements take place in a market supervised by the UN. The EU also plans to expand the bloc’s trading system to more sectors, as well as launch its ambitious carbon border adjustment mechanism[6], a tax on carbon emissions attributed to imported goods that have not been taxed. on carbon at source.

The increase in carbon emission permits also reflects the rise in natural gas prices, which has recently made coal more competitive again. For countries to “phase down” coal – as agreed in the Glasgow Climate Pact – carbon permits would make burning coal more expensive and less attractive to long-term investors.

“Although the outcome [of the COP] was perhaps not as strong as expected, it is still a clear signal that policy makers must take carbon pricing seriously if we want emissions to decrease,” said Mark Lewis. , of the investment fund Andurand Capital.

“There is a general feeling that carbon markets come out stronger from the COP process,” Lewis continues, “as what has become clear is that there is now an acceptance among policy makers that the limited space left for carbon in the atmosphere is the scarcest resource of all.”[7]

The promises of COP 26

Following the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, we wonder when decisions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will have an impact on our climate.

Among the most prominent decisions from this year’s UN climate summit are:

International taxation and climate sustainability

According to the MDPI Institute, the two main international concerns currently being studied by international organizations are the following (1) tax avoidance, mostly by multinationals in relation to corporate tax; and (2) environmental taxation, which is considered key to curbing climate change. For this reason, organizations are trying to develop guidelines for action that can serve as a guide for different countries.[8]

The prospects for a carbon border adjustment system increase the relationship between these two aspects, since the avoidance of the environmental impact of products exported may be linked to forms of tax avoidance.

[1] S&P Global, November 17, 2021: https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/111521-eu-carbon-prices-hit-record-eur66mt-amid -cold-snap-cop26-aftermath

[2] Source: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/11/1105792

[3] https://earth.org/eu-carbon-prices-hit-record-high-following-cop26/

[4] Source: OECD at COP26, November 2021, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/presentation-cop26-carbon-pricing-g20-countries-oecd-november-2021.pdf

[5] The Glasgow Climate Pact is the first global agreement to explicitly include parties committing to reduce the use of fossil fuels, specifically to “accelerate efforts to phase out unretained coal energy and inefficient subsidies to fossil fuels”. Unabated coal power refers to power plants that do not use carbon capture technology, although the term “inefficient subsidies” for fossil fuels was not clearly defined in the final text.

[6] Importers of emissions-intensive goods pay a fee linked to what they would have had to pay had they been covered by European carbon reduction laws in the first place. The price of carbon in the program is at 43.44 euros, the highest point it has reached. It will be limited to a few sectors, with the most likely candidates being energy, cement, steel, aluminum and fertilizers. It will be designed to allow gradual expansion to other industries in the coming years. The mechanism will have to be approved by the European Parliament and by the Member States, a process that could take up to two years. This means that, realistically, the mechanism will not take effect until 2023.

[7] https://www.energylivenews.com/2021/11/16/carbon-hits-record-price-in-europe-following-cop26/

[8] See https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability/special_issues/Taxation_Sustainability

5,601 total views, 12 views today