Analyzing Mandatory Binding Arbitration and the MAP

Introduction

Mandatory Binding Arbitration is an issue that has slowly been gaining attention and on which CIAT Member Countries must work to further develop their official position. Through our experience with developing CIAT member countries, we have identified various positive and negative arguments that may be influential for countries when deciding to adopt mandatory binding arbitration. To provide more objectivity to this analysis we discussed these points through informal conversations with a group of recognized international tax experts; Hans Mooij, Carlos Protto, Enrique Bolado and Álvaro Romano. In this line, this blog post’s objective is to present an overview of some points that could be analyzed by countries when discerning their stance.[1]

History of Mandatory Binding Arbitration

Countries that wish to be part of the Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) must commit to the implementation of the four minimum standards and to having that implementation reviewed. The four minimum standards are found in Actions 5, 6, 13, and 14.

Part of the Action 14 minimum standard calls for countries to adopt in their Double Tax Treaties the first three paragraphs of Article 25, as currently found in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and United Nations (UN) Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital. The wording of these paragraphs effectively opens up the processing of Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP) cases so that they are ‘notwithstanding’ any time limits in the domestic law. Further minimum standard elements include the requirement to provide taxpayers with rules, guidance and procedures to access MAP; to publish the country’s MAP profile and MAP case statistics, among others.[2]

Notwithstanding these requirements, some countries have taken the position that the wording of Article 25 paragraphs 1-3 (in particular “endeavor to resolve”) is not enough to guarantee the effective resolution of disputes. This fact can be further examined using the MAP Statistics[3]

published by the OECD which show the number of MAP procedures that last longer than 2 years and those that do not reach a resolution. Thus, these countries consider it necessary to commit to a binding arbitration clause, as found in Article 25, paragraph 5 of the OECD Model. Furthermore, some countries pushed towards making this clause a part of the Action 14 minimum standard however, the required consensus was not reached making it a recommended practice in the BEPS Action 14 Final Report and one of the optional provisions (Part VI) of the MLI.

More recently, the Inclusive Framework reached an agreement regarding the taxation of the digital economy, to include mandatory binding arbitration as part of the Pillar One Blueprint (topic which is still under discussion in respect of the minimum taxation in Pillar Two).

This blog post will elaborate on issues that are not Inclusive Framework minimum standards but which pertain to BEPS recommendations found in Actions 14 and 15.

Features of Mandatory Binding Arbitration in Part VI of the MLI

At the heart of BEPS Action 15 is the Multilateral Instrument (MLI), a tool meant to lessen the burden of having to individually renegotiate tax treaties, attaining the implementation of BEPS recommendations in existing treaties, collectively and in a shorter time period. The MLI contains the minimum standards, as well as the option to adopt suggested recommendations. The countries choose which provisions of the MLI they want to adopt, they list the tax treaties to which they wish them to apply, they sign and then ratify the MLI to give it legal effect. If their treaty partners also list the same provisions, they are said to match and thus the countries are notified that their treaty has in fact been modified.

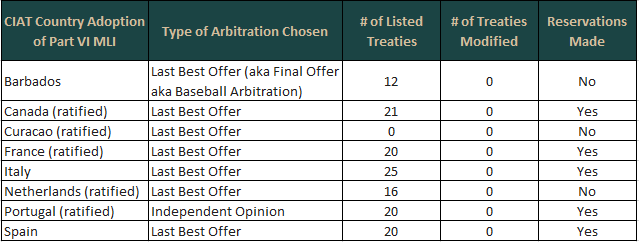

The abovementioned Action 14 suggested recommendation of mandatory binding arbitration can be found in Part VI of the MLI. It calls for baseball arbitration (also known as ‘last best offer’) as the default option. Nonetheless, the MLI provides for flexibility and countries are able to choose the type of arbitration that suits their preference (for example reasoned opinion arbitration), as well as adjusting the scope of the arbitration provision via the implementation of a reservation that excludes certain cases from its reach, among other potential modifications.

It is important to note that the OECD position is to keep mandatory binding arbitration as a last resort, only to be used when cases have been left unresolved by a previous MAP attempt.

Adoption of Mandatory Binding Arbitration in CIAT member countries

As of August 2021, there are twenty-two CIAT member countries that have signed the MLI found in BEPS Action 15, however only ten[4] of these have ratified it.

Out of the twenty-two CIAT countries that adopted the MLI, eight of these countries have adopted Part VI, of which only five[5] have ratified it.

Figure 1. CIAT member countries that have adopted Part VI of the MLI.

Inclusive Framework CIAT member country positions on Part VI of the MLI:

Inclusive Framework CIAT member country positions on Part VI of the MLI:

Furthermore, it could be that some countries have not adopted mandatory binding arbitration in the scope of Part VI of the MLI, but they are nevertheless keen to adopt it through bilateral tax treaty negotiations, protocols, or other type of agreements such as investment treaties. This could be, for example, if a country opposes mandatory binding arbitration when forced on them by a taxpayer but is receptive of the claim when arising by another country (as provided under Article 25(5) Alternative B of the UN Model). Similarly, if a country is opposed against binding arbitration only if it is mandatory but may be inclined to accept it when its voluntary, pursuant to a particular MAP case.

Arguments In Favor and Against Mandatory Binding Arbitration

It is supposed that Mandatory Binding Arbitration provides legal certainty to taxpayers inasmuch as it guarantees that there will be a resolution to any treaty issues brought forth under Article 25. On these lines, it works to encourage authorities to act proactively and not postpone discussions past the time period agreed upon under Article 25 (usually two years) so as to avoid triggering the binding arbitration clause. However, countries are hesitant to adopt this clause for a variety of issues, some of which are further examined below:

Conclusion

There has yet to be seen international interest on behalf of a significant number of countries to adopt mandatory binding arbitration; many of the small island nations and developed countries in general are more inclined to give it a try while the rest are hesitant. It seems including arbitration in their MLI position is less necessary when many of their treaty partners haven’t adopted it either. Furthermore, some countries could cite that there are not enough unresolved MAP cases to justify this.

Even when a country may wish to seriously consider the implementation of binding arbitration, they must take into account what their treaty partners are doing. If their treaty partners aren’t implementing binding arbitration then they don’t get so much in exchange for taking the position in the MLI and its safer for them to adopt it in a bilateral manner, even using it as a negotiation tool if they so wish.

In our opinion, the main weakness of Article 25 as read in the OCDE and UN Models (MAP clause) is the words ‘endeavor to resolve’ which implies no obligation on the part of the tax authorities to reach an agreement. Thus, one option could be to modify the wording in Article 25 to make the resolution of the case between the competent authorities mandatory. This would avoid the need to involve a third party, eliminating additional costs and providing taxpayers with certainty that their case would be resolved. However, this ‘obligation’ to reach an agreement could create a toxic environment that leads to political pressure, especially when a lack of balance exists between the countries being forced to reach an agreement (i.e. negative consequences could ensue for the more vulnerable developing countries).

Another potential option to improve the process of selecting arbitrators is to create arbitration institutes that gives access to more experienced arbitrators from diverse backgrounds, who could be selected via a lottery process, by the countries in order to maintain objectivity.

Another relevant aspect has to do with the interpretation of technical guidance that should be standardized to ensure equal application of international tax rules. In this respect, initiatives that increase the sharing of international experiences are useful. For example, CIAT with the University of Leiden, the financial support of GIZ and technical support from its member countries, is developing a Directory of judicial and administrative decisions pertaining to international taxation. Other options are the OECD’s reports on disputes resolution that contain statistics relating to international tax cases. Along these lines, it could be useful for a country to share their ‘arbitration profile’ (such as the type of arbitration that they prefer, a preselected list of arbitrators, cost restrictions, material to be used as the authority to interpret rules, or other pertinent details).

We recommend that countries make the effort to review their options and make an informed decision instead of simply reacting to what their treaty partners choose. Regional tax organizations increase capacity building so that countries are able to make an informed decision as to what binding arbitration would mean for them. In our opinion, the most difficult problems to solve, given the differences between the countries, are those of a practical nature.

[1] The views expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of CIAT or anyone else hereby mentioned.

[2] See the full Action 14 report here: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/making-dispute-resolution-mechanisms-more-effective-action-14-2015-final-report_9789264241633-en#page1

[3] https://www.oecd.org/ctp/dispute/map-statistics-2006-2015.htm

[4] These ten countries are Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Curacao, France, India, Netherlands, Panama, Portugal, and Uruguay.

[5] These five countries are Canada, Curacao, France, the Netherlands and Portugal.

[6] BEPS Action 14 Peer Review Compilation Report available at: https://www.oecd.org/ctp/dispute/38055311.pdf

10,545 total views, 3 views today

1 comment

Whilst the advice for countries to be more proactive and “make an informed decision as to what binding arbitration would mean for them” is both sage and sensible, I think a critically overlooked aspect of this advice is what is the overall benefit of mandatory arbitration when it is not transparent? For notwithstanding the OECD says mandatory arbitration provides “enormous advantages for taxpayers”, ensuring treaty-based disputes are resolved (which MAP Art 25 does not do), nevertheless, efforts elsewhere suggest that non-transparent arbitration is costly and inefficient. To this end, see 2017 United Nations Convention on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor-State Arbitration (The ‘Mauritius Convention’) which provides a set of procedural rules for making publicly available information on investor-State arbitrations arising under investment treaties concluded prior to 1 April 2014. In which case, why would countries not want to wait and see what happens in this regard before agreeing to adopt mandatory arbitration?