The Impact of International Trade and BEPS Commitments on Tax Incentives and Collection

In memory of Juan C. Gómez Sabaini and Francisco de Paula Gutiérrez

The tax incentive for private investment most widely applied in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) jurisdictions (25) is a lower corporate income tax (CIT) rate in certain industries or specific regions.

If well designed and implemented, the reduced rate is a tool available to governments to foster employment, encourage the transfer of technology and capital, and promote the growth of less developed regions, and it is often applied to export-oriented sectors or zones.

The success of these incentives depends on many factors, one of which is the ability of governments to discriminate between domestic sales and exports with respect to the application of these differential rates. However, many countries have commitments to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) project, which eliminate the possibility of discriminating through these types of incentives between domestic sales and exports for goods and services.

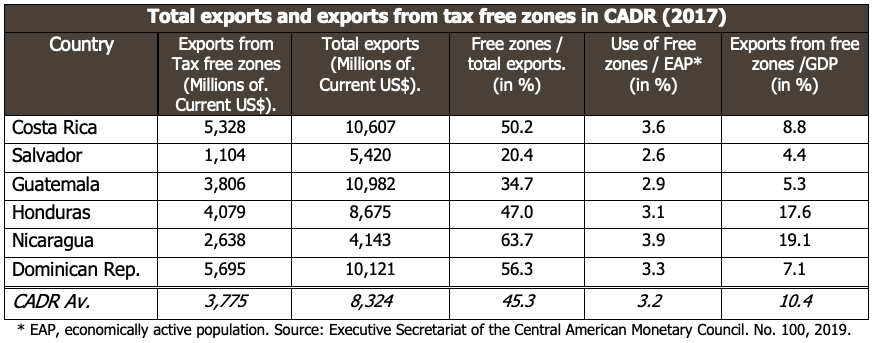

This creates arbitrage possibilities, whose impact on collection can be significant. Currently, the only available statistics on goods exports refer to those from free zones of Central America and the Dominican Republic (CADR), which benefit from a reduced CIT rate. The table below shows their magnitude.

The benefited companies may collude with those in the general regime, mainly, in two ways. One is to overbill goods and services to companies taxed at the statutory rate (thereby reducing the profits of companies subject to a higher rate), while increasing the income of the company that receives incentives. In the second way, the company under the general regime undercharges the goods and services sold to the benefited company. This decreases their profit subject to the higher (general) rate and raises the net income for the company that receives the incentives. This is called arbitrage.

Given the growth of trade in general and, especially, of services in the digital economy, this arbitrage has an increasingly significant effect on collection, because these types of services can be provided to almost all sectors and are more complex to control and assess for the tax administration.

The consequences on domestic competition are also negative. Over time, benefited companies can offer more competitive prices because they pay less income tax, thereby eliminating competition among non-benefited companies and further reducing revenue for governments.

In this context, countries are now facing a serious dilemma: if they do not want to give up revenue, they must choose between applying tax incentives or accepting the (two) international commitments mentioned above. Trying to achieve all three things at the same time (completing this “trilogy”) is not a priori possible.

Three Policy Alternatives for Tax Incentives

Governments may implement any of the three Policy Alternatives[1]described below to reduce the possibility of arbitrage for benefited companies, so as to mitigate revenue losses—and its consequences for equity—while respecting international commitments.

These treatments do not guarantee horizontal tax equity or fair competition within the country between incentivized and non-incentivized companies, but they mitigate the asymmetries that give rise to arbitrage and are relatively easy to administer. The proposals above are not exhaustive, and can be improved, because there is no hiding the risk that they may not meet current BEPS standards on ring-fencing (Action 5).

Solving the Impossible Trilogy: International Commitments, Tax Incentives, and Tax Sufficiency

On the one hand, governments will not stop using tax incentives to promote development in the short term; on the other, WTO and BEPS commitments are also here to stay, therefore arbitrage is a problem on the rise. This is the more relevant, as neutrality in the treatment of income taxation between sales, whether exports or the domestic market, is gaining ground, in compliance with international commitments. However, given the increasing weight of digital and high technology industries, which are usually beneficiaries of tax incentives, governments must choose between keeping benefits (e.g., free trade zones), foregoing revenue, and leaving companies in the domestic market at a disadvantage; or eliminating the incentives, possibly hurting their policies of investment attraction (and even innovation) and generating a conflict (for non-respect of acquired rights).

Fortunately, international taxation fora, with the support of multilaterals led by the OECD, aware of these major challenges, have successfully promoted international coordination by designing special solutions for certain groups of countries.

This “impossible trilogy” may indeed be unravelled. To that end, it will be necessary to apply in the short term, together with overall BEPS solutions (duly loosened up for emerging economies[2]),some of the three practical options described above, which enable the use of tax incentives as a policy tool within the framework of multilateral recommendations.

This blog is a summary of the article “Tax Incentives, International Commitments and Tax Sufficiency: Another Impossible Trilogy“

[1] Other types of alternative incentives for the promotion of the knowledge economy or other specific investments may be considered, such as granting tax credits against income tax for (a percentage of) employer social security contributions paid and, more specifically, the so-called IP Box for royalties: Under certain “substance” conditions, a harmonized incentive among OECD jurisdictions which allows for sharp reductions in the tax base of the income from the results of scientific research, technological development, or innovation.

[2] For example, including flexibility in Action 5 and Global Anti-Base Erosion (GloBE).

6,204 total views, 9 views today