The future of transfer pricing for developing countries

One of the lessons that the pandemic has left us is that, in the near future, the context may change radically and we must be prepared to face these changes. This is related to the importance of history as a science that allows us to know the past in order to understand the present and plan for the future.

This is precisely what I am going to refer to in this post, in particular, the future of transfer pricing. starting from a general analysis of the history of transfer pricing in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and the situation of 23 countries in the region. For this, I have consulted updated data between 2020 and 2021, from the CIAT Transfer Pricing database. These data are currently on file with CIAT, and we hope to publish them soon.

Since 1992, the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean have gradually implemented regulations to address the risk of abusive manipulation of transfer prices or technical differences derived from transfer prices, with an impact on the determination of taxes. Paraguay is the latest LAC country to adopt rules based on the Arm’s Length Principle, incorporating them into its tax system in 2019. To date, some countries have not yet implemented these type of norms; among them, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Bermuda (does not have income tax), among others.

Many of the regulations implemented in LAC countries have undergone reforms with the aim of modernizing or optimizing them (e.g.: Mexico, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina, Costa Rica, Panama, etc.). Recently, between 2019 and 2021, several countries have adopted measures inspired by proposals from the BEPS Action Plan: Action 8 (Ecuador, Mexico, Argentina, Costa Rica, and Honduras), Action 9 (Ecuador, Mexico, Argentina, Costa Rica, and Honduras), Action 10 (Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Honduras, Argentina, and Costa Rica), and Action 13 (Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru, Brazil, Chile, Panama, Bermuda, Belize, and Uruguay)[1].

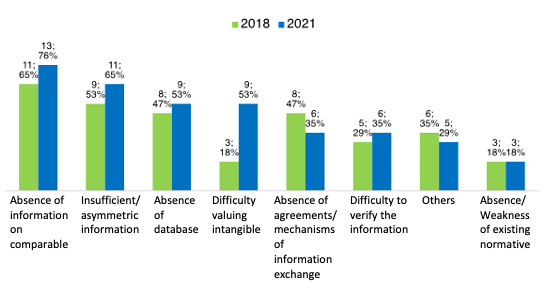

Some countries have been more successful than others in controlling transfer pricing, which depends mainly on the human and material resources available in the tax administrations, capitalized experience, the characteristics of the regulations, the political will to address this issue, and their ability to address tax planning, among other aspects. In general, there is no linear relationship between the years of experience (since the rule came into force) and the results achieved. However, for many countries barriers persist that have lasted over time and even increased. The following graph, prepared with information provided by LAC tax administrations, available in CIAT databases, presents the incidence of these barriers during the transfer pricing control process, for the years 2018 and 2021.

Source: Prepared by the author with the information provided by 17 LAC countries

Source: Prepared by the author with the information provided by 17 LAC countries

We can observe that the absence of comparables, despite international efforts to create support tools for tax administrations, new information regimes, the product of international collaboration and access to more and better information thanks to the exponential increase in networks of agreements for the exchange of information for tax purposes, has increased by 11 points, from 65% to 76%. This may be due to the additional difficulty that the impact of the pandemic and its associated measures on business has contributed to the analysis.

Similarly, for a large part of the countries, insufficient information or its asymmetry constitute an impediment when carrying out controls. This can be related to the availability of information, but also to the information provided by taxpayers. This barrier has been increased by 12 points.

The absence of databases has to do with the lack of useful public information for transfer pricing control and with the difficulty that tax administrations face in acquiring commercial databases. This problem has also increased, but to a lesser extent, 6 points.

The biggest problems that tax administrations face are related to the availability and access to information. However, one of the most significant problems, which has increased by 35 points, is the difficulty in valuing intangibles. This is striking, given the contributions provided by BEPS Action 8 to identify and value them. However, the proliferation of more and new intangibles, especially in the field of the digital economy, may have added more complexity to the analysis.

For the aforementioned reasons, it is logical that the “absence of agreements and mechanisms to exchange information” has decreased by 12 points. Likewise, the difficulty of verifying information has increased by 6 points. Perhaps it is the product of the greater amount of information that is currently generated and that must be analyzed with the resources available in the tax administrations.

It is to note that the barrier “absence and weakness of regulations” has not changed between 2018 and 2021 when more international proposals on how to improve legal and administrative rules are available (For example, the actions corresponding to BEPS transfer pricing issues and the Cocktail of measures for the control of harmful transfer pricing manipulation, focused within the context of low income and developing countries by CIAT, published in 2020, among others). Many countries, as discussed above, have had the opportunity to adopt reforms and even to provide feedback thanks to improvements in their risk management systems, which could promote decision-making on reforms to strengthen the transfer pricing regime.

Another problem, which is observed when evaluating the regimes of the LAC countries, is the asymmetry of norms for the control of transfer prices. At first glance, almost all the countries adopt the Arm’s Length Principle and the methods of the OECD guidelines, but the asymmetries are clearly seen in the definition of the criteria that determine the obligation to comply with the price regime of transfer; and in particular in the criteria to prove or presume linkage, or in the thresholds defined for this purpose. Asymmetries are also perceived in the scope of application of the rules, as only some countries consider the possibility of applying the regime to domestic transactions between related parties. Likewise, there are asymmetries in the legal possibility of selecting an analyzed part that is located abroad, which constitutes an important barrier to applying the best method rule correctly in all cases. Penalty regimes also have different levels of effectiveness, and the definition of tax havens or lower taxation is also asymmetric. There are, in turn, some asymmetries in the information regimes, in the possibility of carrying out certain adjustments, and in the deadlines applicable to the control procedures. All this is added to possible differences in the administrative or judicial criteria, related to the interpretation of the rules.

Likewise, the networks of treaties to avoid double taxation have grown, but have not spread widely in LAC countries, making it complex to avoid double taxation, even if the rules are consistent between two countries.

Among the common denominators, the indiscriminate use of unilateral methods stands out, in particular the Transactional Net Margin Method, the existence in several countries of methods or mechanisms to deal with cases of import/export of raw materials, although not all have experience in their implementation, and very limited resources to manage risks, carry out controls and implement audits. This, without prejudice to the fact that the capacity of many tax administrations to deal with this matter has been significantly increased.

Given this scenario, I wonder how transfer pricing control could be addressed in the future? The answer is complex, somewhat subjective, and could even depend on the characteristics of countries or groups of countries. In my experience, and with the aim of feeding this discussion, I raise some – not all – aspects on which I think it is convenient to pay attention:

I am aware that several of the aforementioned points are known by many. They require the strengthening of other basic aspects of the tax administration, and not all of them are necessarily innovative -because they have been developed in various documents, and even implemented by countries-, however, I believe that for most LAC countries (and even other regions), these issues should be observed with sufficient attention at the time of setting out their agendas or action plans.

[1]Source: BEPS monitoring. CIATData.

[2]CIAT and GIZ (2019). Cocktail of measures for the control of harmful transfer pricing manipulation focused within the context of low-income and developing countries.

7,222 total views, 3 views today