Digital Services Tax (DST)

While the digital economy was gaining more and more space within the global economy, its taxation was also gaining center stage. In this way the countries began to see that value was generated in their territories by their data and the contribution of their users, but the multinational companies were taxed in other jurisdictions, specifically in those of low taxation with the subsequent remission of these profits to tax havens.

To avoid this plundering of their public coffers, many European countries took the lead in reaching an international consensus for the revision of the current tax regulations, especially the concept of (digital) permanent establishment, which would allow them to tax this income within the Corporate Taxation.

In the absence of consensus within the OECD, the European Commission proposed an indirect tax on the provision of certain digital services. France was one of the European countries that most pushed for a ‘Google tax’ throughout the European Union, something that finally did not materialize due to the opposition of Ireland, Denmark, Sweden and Finland.

In the face of the failure of multilateral imposition, only the path of unilateral imposition remained. Thus, in 2019, France imposed a tax on digital services (taxe sur certains services fournis par des grandes entreprises du secteur numérique).

It was colloquially called the GAFA tax in France because it was intended to tax the income of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple. Although its object includes some thirty digital multinational companies, the main ones being of North American origin. In Italy it is known as “Web tax” and journalistically as “Google tax”.

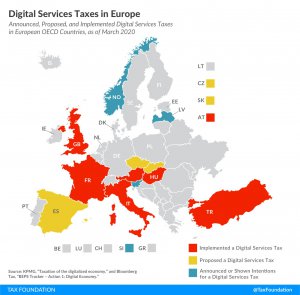

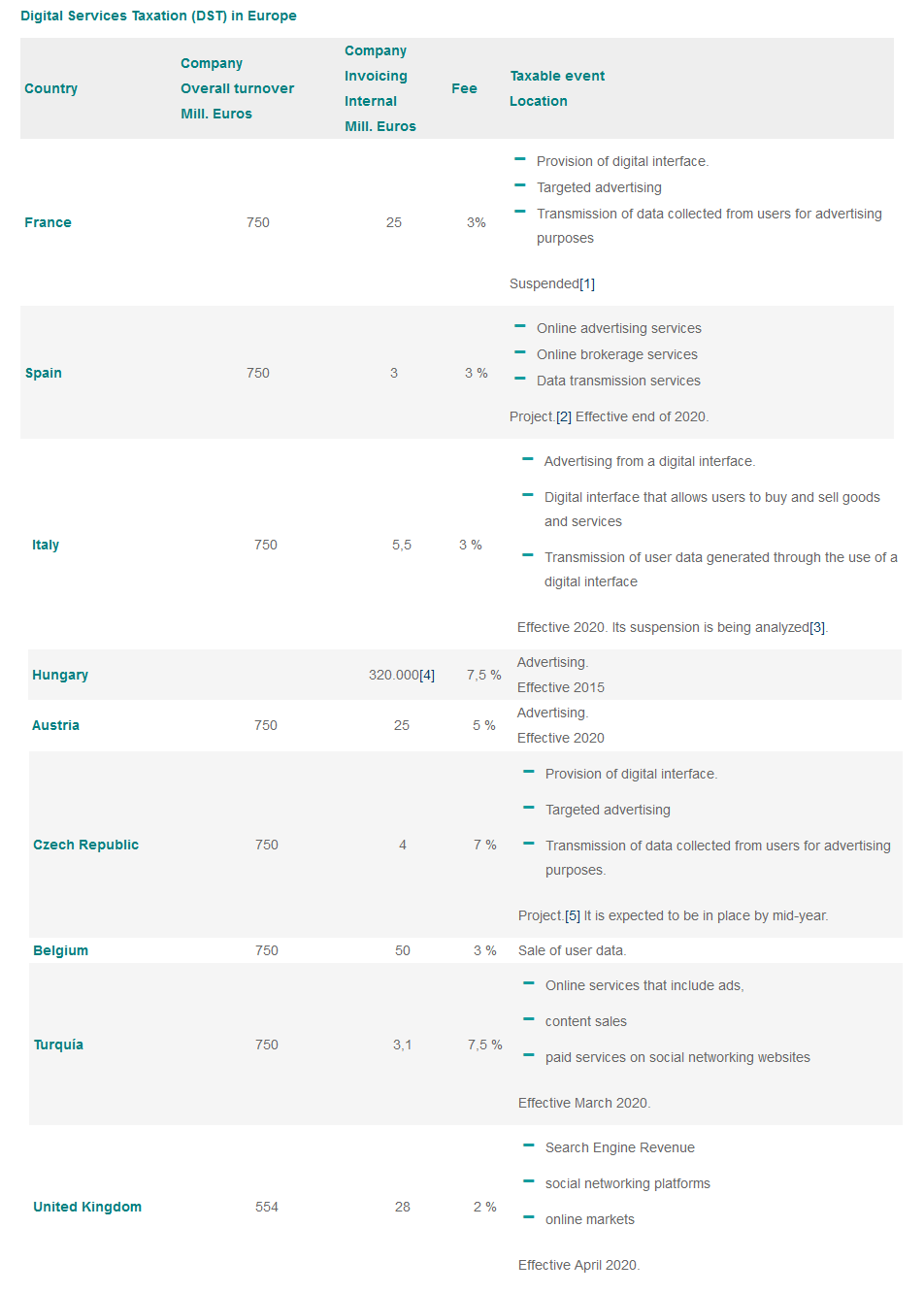

After a year (2019) of studies and marches or actions in favor or against, the current trend is to implement it, so below are the European countries that have implemented this indirect tax or are planning to do so:

Source: own, from the European Commission (2019) in the report “Tax policies in the European Union” and from KPMG, “Taxation of the digitised economy”, updated on 21 March 2020

In Europe, Latvia, Norway, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia have announced that they intend to implement this tax. In the international order, Chile, South Korea and New Zealand announced this intention.

As the general trend of European taxation can be seen (with some exceptions), it has the following characteristics:

The story will continue to unfold, but as long as there is no international consensus to change the current concept of permanent establishment to a digital one that allows countries to tax digital multinationals on income tax, this tax is a legitimate form of taxation.

If we look at the tax strategy of the countries of Latin America, it has been different. their objective was to tax certain digital services from abroad for being used in their countries in the Value Added Tax, with the subjects of the tax being the users, with definitive withholding by financial institutions, cards, etc. when making the payment.

In times of the current economic crisis as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, where tax revenues are declining while expenditures are increasing to minimize the economic downturn, meet health expenditures and satisfy basic social needs, it would not be unwise for the tax policy makers in the region to examine the European experience.

There are reasons based on equity, fiscal sustainability and above all common sense in requiring digital multinationals to meet their tax obligations in the countries where they earn their income.

[1] It only lasted one month, November 2019. France repealed it in the face of the US government’s threat to increase import tariffs on sensitive French goods, because it considered the tax a persecution of American companies.

[2] It’s been in the courts since January 2020.

[3] It is analyzed to follow the strategy of France, to avoid commercial retaliation from the USA.

[4] That’s 320,000 euros a year in revenue. The millions don’t apply.

[5] In parliamentary committee.

12,915 total views, 16 views today