Fiscal Policy and Economic Recovery in times of Pandemic

The best projection is uncertainty. This phrase, pronounced during the press conference organized by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its presentation of its latest publication on the perspectives of the world economy, during the second week of April of this year[1], summarizes very well what is currently known with respect to the socioeconomic consequences of COVID-19: almost complete uncertainty. Everything will depend on the evolution of the pandemic, the policy measures being adopted by the countries, but also on the structural characteristics of the latter and the unforeseen reactions of the population.

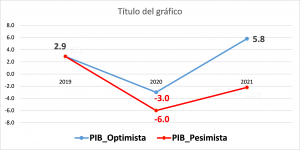

The most optimistic scenario in the IMF’s projections; that is, its “base scenario” assumes that the pandemic and the necessary restraint will reach its maximum point in the second quarter of the present year, in the greater part of the countries of the world and will fall back in the second semester. According to this optimistic approach, the IMF estimates a 3% contraction in the world economy in 2020. The surprising aspect of this projection is that only in January of this year the IMF had already adjusted its estimates of October 2019, projecting a world growth of 3.3% in 2020 and 3.4% in 2021: a drastic change in such a short period of time! According to the IMF, we are facing the worst recession since the great depression of the 30s in the past century.

It is projected that this year, the advanced economies will experience a contraction of -6.1% while for the emerging markets and developing economies it will be -1.0% (if China is excluded the contraction will be -2.2%). The per capita income will be reduced in over 170 countries. We are thus faced with a generalized recession.

Latin America and the Caribbean are not the exception and it is estimated that the region’s GDP will be reduced by -5.2% during the present year. Brazil and Mexico are among the most affected economies, with contractions of -5.3% and -6.6%, respectively. In the case of Argentina, ECLAC (2020) [2] estimates a contraction of -6.5%. In Peru, the Ministry of Economy and Finance projects a contraction close to -6.0%, although independent research centers estimate that the downfall will be close to two digits.

According to the IMF’s optimistic scenario, provided that the policy measures adopted by the governments of the world may serve to avoid generalized bankruptcies, loss of jobs and systemic financial tensions, the world economy would recover in 2021: the GDP would increase by 5.8%. The recovery would be more evident in the emerging and developing economies (6.6%) as compared to the advanced economies (4.5%). Latin America and the Caribbean, in particular, would show a 3.4% recovery.

However, the IMF also includes in its projections two other pessimistic or adverse scenarios which consider the assumption that the pandemic will not decline in the second semester of 2020, or will extend until 2021. In said scenarios, the world’s GDP could contract -respectively- by -6.0% in 2020 and the estimated growth would turn negative in 2021. It goes without saying that this is the most probable scenario.

Graph 1

COVID-19: Effects on world’s GDP

Source: IMF (2020a).

Source: IMF (2020a).

Prepared by the author.

The originality of the crisis

We are not simply faced with another crisis. ECLAC (2020) estimates that the decrease of Latin America’s GDP (-5.3% in 2020) could even be more severe than the one that occurred during the great depression of the 30s or at the beginning of the 1st World War (1914). With an additional ingredient of originality: none of the two economic crises mentioned had a pandemic disease as trigger. On the contrary, the research made regarding the relationship between the health of the individuals and the economic crises concluded that -for example- the great depression of the 30s was not associated with a greater deterioration in the health of the population. It is not a simple anecdote, but rather a determining factor that will influence the economic recovery.

The socioeconomic effects

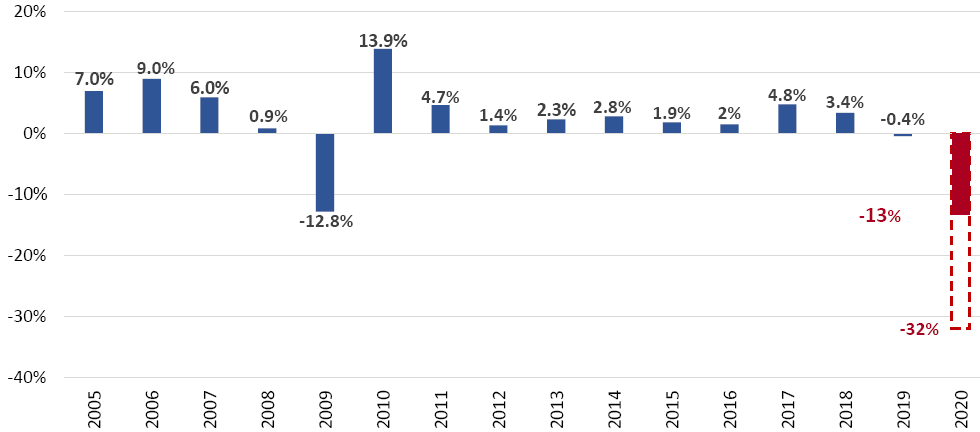

The social distancing and isolation measures which the countries have been implementing to face the pandemic have generated a vicious circle, which began restricting the national supply and demand, to then result in a lower supply and demand in international trade. The World Trade Organization (WTO)[3] estimates a downfall in the volume of world trade of goods between -13% and -32% in 2020, a much stronger contraction than the one registered during the 2009 financial crisis (-12.8%).

Graph 2

Volume of world trade of goods (inter-annual variation rate)

In the labor area, by April 7 of this year the International Labor Organization (ILO)[4] informed that the total or partial lockdown measures already affected close to 81% of the world’s labor force (close to 2 700 million workers). According to this organization, in many countries there is already an unprecedented large-scale employment contraction.

The loss of jobs in 2020 will be very high, since 38% of the world’s active population[5] (1 250 million workers) are employed in sectors which –due to the pandemic- are facing an acute downfall in production. Some of the most affected sectors are retail trade, accommodation and food services and the manufacturing industries.

In the developing countries, the pandemic and its socioeconomic effects have resulted in greater poverty: ECLAC (2020) estimates that in 2020, poverty will increase in 28 million individuals in Latin America, while extreme poverty will do so in 15 million individuals. These figures should not come as a great surprise, inasmuch as the ILO (2020) reminds us that close to 2 000 million individuals in the world work in the informal economy, the greater part of them in developing countries. That is, millions of individuals who are not necessarily receiving the government’s social aid, simply because it is mainly being channeled through instruments and according to “formal” data bases which obviously do not include the most vulnerable segments of the population that survive in informality.

The socioeconomic effects of the pandemic within the very short and medium term, will be determined by what each country is doing or failing to do. They will also -or mainly- be determined by what was done or not done in the preceding years or decades, which reaches a dramatic dimension in the case of the developing economies. We refer, in particular, to the little investment of these countries in health infrastructure and services, in social security and pensions, for example.

The policy alternatives

The originality of the current economic crisis, on being caused by a virus and the subsequent measures adopted to try to control it, explain the reason why the governments’ first reaction has been to prioritize the health policies and the social distancing measures that have been extended, in the hope of achieving a stage wherein the rate of increase in the number of infected persons may begin to decrease.

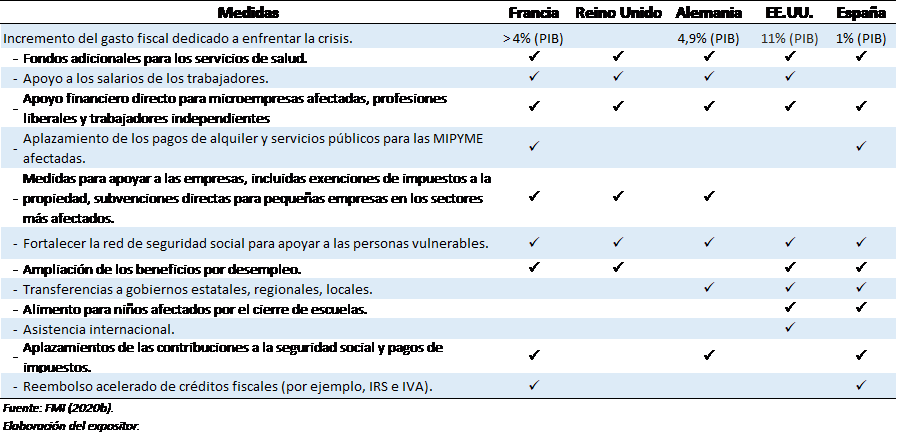

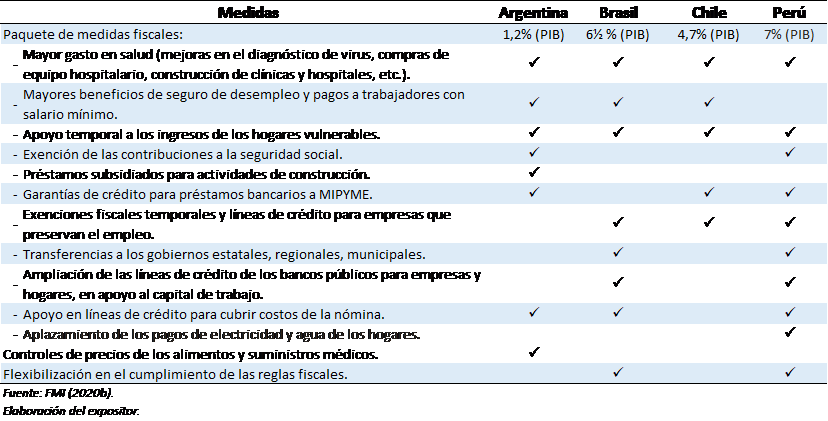

On observing the economic policy measures being applied by the countries[6], the first thing that becomes evident is their great similarity with respect to the monetary instruments, but above all in relation to fiscal policy. The difference lies in the degrees of freedom in their implementation, which are determined by the countries’ income level. In contrast to the broad display of resources by the developed countries for facing the pandemic and its socioeconomic consequences, in the developing countries the fiscal margin for economic incentives is quite limited.

Chart 1

Fiscal policy measures in developed countries

Source: IMF (2020b).

Source: IMF (2020b).

Prepared by the author.

Chart 2

Fiscal policy measures in Latin America

Source: IMF (2020b).

Source: IMF (2020b).

Prepared by the author.

The difference does not end there. While in the developed countries the fiscal resources being provided are contributing to reinforce the health systems, whose effectiveness began to be developed since the end of the Second World War, in Latin America and the Caribbean -with very few exceptions- the scarcity of said systems is alarming. It is impossible to build in a few weeks what ceased to be done for decades. Therefore, the financial resources are doubly insufficient in these countries. Another great difference is the effectiveness with which the countries implement the policy measures.

In fact, COVID-19 ends up being a Pandora box which, showing in a single stroke all of Latin America’s structural problems. There is not only a lack of an adequate health system, but this also brings to light problems of public expenditure management, corruption, excessive centralization, low banking level, informality, among other restrictions. It is a matter of previously existing structural problems, already theoretically considered by Prébisch and ECLAC since the 50s and 60s of the last century. It is true that, since then, there have been substantial changes in the Latin American economies, but can someone deny that not a few of those structural restrictions still exist in not a few countries of this region, the most unequal of the world? This merely limits the effective implementation of the economic policy.

For example, like in the developed countries, in Latin America the governments are providing economic aid to the population, but to the extent that a large segment of the latter does not use the financial intermediation services, they must go to the banking network to collect the aid in a face-to-face manner, which has only increased the levels of infection in some countries. In Peru, a particular event worsened the levels of infection: in view of the unemployment and an economic aid that is not received with due promptness, thousands of country people began to return from the capital city to their places of origin, thereby increasing the risks of infection. No one had anticipated this social reaction.

The developing countries, and within them the lower revenue segments will be the ones mainly affected by the pandemic. The lower revenue sectors are the most prone to the disease, not only because of their deficient nourishment, but also because most of them operate in an informal economy that allows them to survive day by day. Confinement has deprived them of their daily revenues, the government’s economic aid does not arrive or is insufficient; therefore, they are obliged to circumvent the sanitary controls to try to sell some of their products and/or obtain provisions in those markets that offer the lowest possible price, but which are also the main sources of infection. They fear hunger more than the virus.

Fiscal revenues and the tax administration

Amidst such an economic scenario, which was already quite uncertain at the global level even before the pandemic, the recovery of fiscal revenues will be delayed. How long? It will all depend on the control of COVID -19 and the speed at which the productive system may recover, since the GDP has a direct effect on the fiscal revenues. The close correlation between both variables is not the subject of discussion, rather what can be argued is the magnitude of the effect. That is, if there is no economic recovery, there will be no fiscal revenues either, which situation is particularly worrisome for a region such as Latin America, whose tax pressure is already structurally low.

The fiscal relief measures (for example, postponement of tax obligations) and tax benefits (such as, reduction of depreciation periods) which the governments have been implementing in a generalized manner to mitigate the effects of the crisis on the businesses and individuals, add up to the negative effect on collection caused by the lower economic activity. Expenditure is increased, but fiscal revenues do not arrive or are not collected. How can we square the circle? There is no other way out, but through indebtedness, which will limit the economic recovery.

Although the current crisis is the result of a discretional decision of the governments, with the major objective of avoiding serious consequences in the health and life of the individuals, to retrace one’s steps will not be at all easy, to the extent that the source of the problem is not eliminated or at least controlled. That is, until a vaccine or medicine is found for achieving said objectives. This increases the uncertainty and weakens the effectiveness which -in contexts of “normal” economic crises- is attributed to economic policy instruments.

At the outbreak of the 2008-2009 world financial crisis, economists considered that it was the worst economic crisis since the 30s, but -it was said- that the great advantage for the world was that there were already better economic policy instruments to face it. It happens that, we now know it, said crisis was not -by far- as strong as the current one, and -contrary to that situation- the effectiveness of the policy instruments is subordinated to the success achieved in the containment of COVID-19. The countries may begin to render flexible the restrictive socioeconomic measures adopted during the pandemic, but it is not very probable that the economic agents, on the side of the demand may react at that same pace of enthusiasm. The Law by J.B. Say, according to which every supply creates its own demand, was already surpassed a long time ago.

In this context, the degrees of freedom of the tax administrations for improving the collections levels are somewhat limited. With the greater part of their officials being unable to carry out their regular functions, the tax administrations are working half-heartedly. Teleworking has been very useful, but not all functions of the Administration may be carried out that way (field auditing, for example). Their main function, control and examination, must look for more creative ways and prepare for what is coming: in times of crisis, tax noncompliance is worsened.

The seriousness of the current health and economic crisis at the world level, leaves very little margin for the policy alternatives favored by the market (as determined by the neoliberal doctrine). The world has thus understood it and is opting for measures based on the State’s regulating role. In this context, the tax policy and tax administration must undertake a significant change in the logic with which they have been generally operating. The current situation is not necessarily in favor of collecting more, but rather of trying to collect better, favoring the service to the taxpayers and citizens, without disregarding a more focused examination (Big Data and the ICTs must be used to their maximum capacity), that may respond to the challenges imposed by the “new times”.

[1] IMF (2020a). World Economic Outlook, April 14, 2020.

[2] ECLAC (2020). Latin America and the Caribbean: Dimensioning the effects of COVID-19 to consider reactivation. Presentation by Alicia Bárcena, April 21, 2020.

[3] Taken from ECLAC (2020).

[4] ILO (2020). ILO Observatory – second edition: COVID-19 and the labor world; April 7, 2020.

[5] The active population is 3 300 million workers.

[6] See: IMF (2020b). Policy responses to COVID-19. Policy Tracker. Last updated April 10, 2020.

13,012 total views, 18 views today

1 comment

Es imprescindible que las autoridades expliquen permanentemente a la opinión pública el daño económico que se está produciendo, tanto por las restricciones sanitarias como por el impacto de la crisis económica global y local.