Leveling the playing field in times of crisis: Indirect taxation on the digital economy in Latin America and its potential revenue

In memoriam Juan Carlos “Bebe” Gómez Sabaini, teacher and friend

The digitalization of the economy has led to important changes in business models and in the value-creation processes of companies. From the fiscal point of view, a series of challenges arise, since tax systems, designed for another era and circumstances, present a series of weak points that favor the erosion of tax revenues from these new models.

On the other hand, it is well known the need of the governments of the region to strengthen their tax revenues to face the structural challenges summarized in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and those derived from the COVID19 crisis. It is in this framework and considering the importance of ensuring a correct taxation of the digital economy, both in relation to direct and indirect taxation, that we have recently prepared a study (Indirect taxation on the digital economy and its potential revenue in Latin America. Leveling the playing field in times of crisis / 2021) in order to analyze the indirect taxation options of the digital economy and its potential impact on tax collection in Latin American countries.

Digitalization has allowed some companies to participate actively in certain economic sectors in other countries, without necessarily having a significant physical presence there. On the side of indirect taxation, and Value Added Tax (VAT) in particular, there is the difficulty in taxing transactions at the place of consumption, especially in the case of digital services and intangible goods since the seller resides in another jurisdiction.

One of the consequences of the confinement by the pandemic of 2020 has been the significant growth of the digital economy, through consumption via digital platforms that in several countries of the region is not yet taxed or, at least, not to the desirable extent.

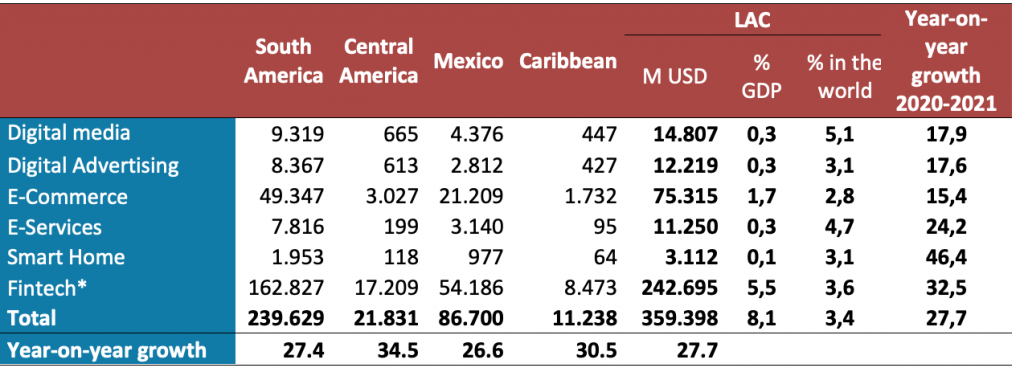

Beyond the limitations and difficulties to measure it, below there is an estimation of the digital economy and its growth in the last year, by sub-regions, and considering the following sectors[1]: market of e-commerce of physical goods (e-commerce); market of electronic services (eservices); digital advertising; digital media (content, digital video, digital music, digital games, e-books, newspapers, etc.); Smart Home, and FinTech (Financial Technology, although only includes the segment of digital payments). It is estimated that the revenues of the digital economy in the region would grow 28% annually in 2021, reaching USD 359.4 billion, equivalent to 8.1% of regional GDP, compared to 11.2% of GDP for OECD countries.[2] As can be seen, the digital economy has become increasingly important in Latin America and the Caribbean, accounting for approximately 3.4 per cent of global revenues from the digital economy by 2021, while Latin American electronic commerce of goods would account for 2.8 per cent of global sales.

Table 1. Latin America and the Caribbean. Size of the digital economy by subregion-2021-in millions of USD and percentages

Source: Jiménez and Podestá (2021) based on Statista – https://www.statista.com/outlook/digital-markets

On the other hand, the impact of the pandemic on the fiscal accounts, which leads to requiring higher public spending, but with a lower generation of tax revenue by the fall in the level of activity, has strengthened the need to increase revenues and makes it urgent to tax the digital economy through the implementation of VAT (and also any solution of global consensus on income tax).

The non-taxation of these transactions not only has a significant cost in terms of revenue but is also creating strong unfair competition with traditional sectors, especially against small businesses, precisely those most punished by the crisis.

In view of the rapid growth of the digital economy and cross-border transactions, it is crucial that countries adapt their VAT laws to tax services and intangible goods acquired abroad by resident businesses and consumers, while providing for adequate mechanisms for collecting and registering taxpayers.

As a way to support this objective, the OECD, together with the IDB, the World Bank, and the CIAT, are developing a set of application guides (“toolkit”) for Latin American and Caribbean countries to facilitate the implementation of the proposed recommendations on this matter. For its part, CIAT, with financial support from NORAD-cooperation of Norway – is developing a computer tool that will allow the administrations of countries that wish to use it, the effective implementation of this approach (The Digital Economy, the Norwegian Cooperation and CIAT. An Essential Tool).

The adaptation of indirect taxation, in order to tax the digital sector, is key both to obtain tax revenues and to “level the playing field” with local suppliers so that they operate on equal conditions of competition. Otherwise, the loss of tax revenue will be increasingly important, not only for the expansion of this sector but because companies in traditional sectors will seek to migrate into the digital sector and operate from the outside, with consequent damage to employment, economic growth, and the development of the local economy.

Given this scenario, some Latin American countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay and Uruguay) have incorporated digital services into the VAT tax base and have begun to collect the tax, although the rates, the collection mechanism, the mandatory registration of the provider and other characteristics of the tax vary between countries.

From a collection point of view, these countries have obtained tax revenues for this concept that are between USD 20 and USD 120 million per year, depending on the size of the digital economy of each country, which is equivalent to a value between 0.02% and 0.04% of GDP (Table 2). However, in some cases, as in Chile, the values included in the table correspond to the first six months of application of VAT, so when you have the collection of a full year this indicator would approach 0.08% of GDP.

Table 2- VAT collection for digital services in Latin American countries

** / SRI estimation.

Source: Jiménez and Podestá (2021) based on official figures.

While the recommendation of experts and international organizations with respect to business-to-consumer (B2C) transactions is that the foreign supplier company register as a VAT taxpayer, through a simplified process, in the jurisdiction of the buyer and be responsible for collecting, reporting, and paying the tax, countries with smaller markets may face difficulties in forcing foreign companies to register and sanction them in case of non-compliance. Faced with this difficulty, some Latin American countries have chosen to charge VAT on digital services acquired abroad, through withholding systems in payment methods, an approach that also has a series of problems and limitations.

From the review of the emerging literature, the recommendations of the international organizations, and comparative experiences it can be concluded that the best suggestion for the countries of the region that have not yet implemented measures to tax with VAT on cross-border digital services, is to opt for the system of compulsory registration in VAT for suppliers who are not residents, combined with the withholding tax on the means of payment only in transactions with suppliers that do not comply with the obligation to register.

To this end, it is essential that tax administrations carry out a detailed and exhaustive identification of the companies that potentially should register, a list that must be updated periodically. This list will be necessary to request the voluntary registration of suppliers and, if this does not happen, inform the issuers of means of payment to which companies the withholding should be made.

With regard to the definition of digital services in the regulation, it is advisable to use a broad concept of digital services, without prejudice to the fact that some of them may be exempted under the general exemptions provided by VAT legislation at national level.

In addition, in the case of establishing specific exemptions for certain digital services, in order to grant certain incentives, it is important to ensure that such exemptions are also extended to national suppliers, so as not to encourage unfair competition.

The general recommendation regarding VAT is to tax completely at the place of consumption, which means that the commissions charged by the administrator of a digital platform must be one hundred percent taxed by VAT. But, in addition, any digital service that is consumed in a country must be taxed with this tax.

It is also suggested to facilitate the registration of non-resident suppliers, through a web platform and a simplified procedure, which does not require the physical presence of the company’s representatives.

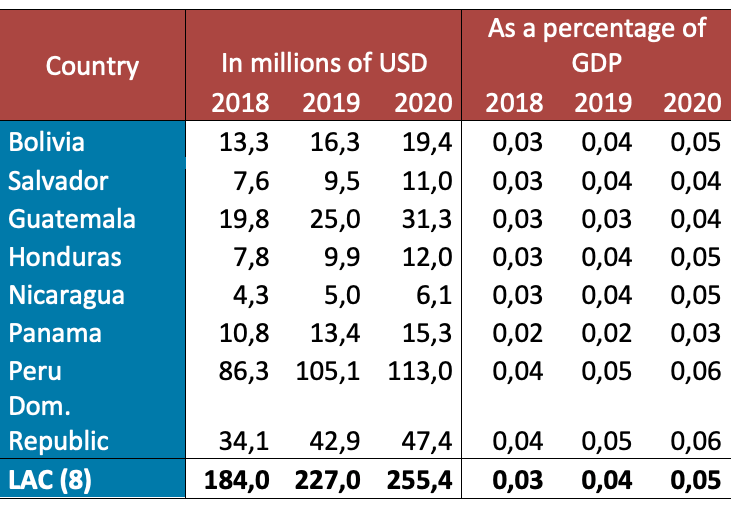

In Jiménez and Podestá (2021), estimates of the potential of VAT revenue on digital services are made in those countries that have not yet applied this tax to the sector (Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, and the Dominican Republic). The potential collection in terms of GDP would be comparable to that achieved by the Latin American countries that already tax these activities: between 0.02 and 0.06 percent of GDP annually and once the tax is fully implemented. According to the degree of penetration of these technologies, the size of the countries and the VAT rate, the annual resources that could be obtained in the countries where the tax is not yet collected range from $ 6 million in Nicaragua to $ 113 million in Peru.

Table 3 – Latin America (8 countries). Estimation of the potential of VAT revenue for digital services. 2018-2020

Source: Jiménez and Podestá (2021) based on the reports of these companies to US – SEC and IMF and ECLAC for data on population, GDP and per capita income.

Finally, it is important to highlight two elements that have not been considered in the estimates and that would broaden the effect on potential collection.

Firstly, it has not been measured here how much VAT collection would fall in those countries that do not change legislation and continue without taxing cross-border digital services. The fact that these services continue to expand and may not be taxed prevents competition on equal terms and implies increasing damage to tax revenues, the economic activity of resident companies that are taxpayers, as well as affecting employment and the informal economy. The negative impact on the income of local businesses will clearly affect the future levels of revenue, the effect will be even greater if local businesses or traditional sectors are seeking to move into the digital sector and operate from abroad, which would increase the loss of revenue even more.

The second element that allows us to assume a greater effect on revenue is related to the intermediary platforms of accommodation and transport services (such as Airbnb and Uber), since the estimates have only included the VAT that would be generated for the service provided by these intermediaries, that is, for the commissions that these digital companies charge to their customers or users. However, since in many countries the platforms share with tax agencies the information of the owner or lessor of the property and the driver, as well as the income they receive, this will also strengthen the VAT collection for accommodation and transport services and the income tax of hosts and drivers.

[1] For more details on the segments included in each sector, see https://www.statista.com/outlook/digital-markets

[2] This OECD value corresponds to an estimate for 2020 published by the IDB (Del Carmen et al., 2020).

5,373 total views, 2 views today