A look at the commitment of the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean to combat the tax base erosion and profit shifting

In 2019, and in response to numerous requests from member countries and organizations, the CIAT decided to add to CIATData (service that groups the CIAT databases), information on the situation of its member countries regarding the adoption of recommendations derived from the BEPS Action Plan.[1] In recent years this information has been updated, reflecting in a timely manner the individual progress of each country that makes up the sample.[2]

The information that integrates this Database, called “BEPS Monitoring”, was provided by the tax administrations of 37 CIAT member countries, from Latin America, Africa, Asia and Europe. The “BEPS Monitoring” provides tables and graphs with details on the total or partial adoption[3] of recommendations or “measures” that integrate each of the actions of the BEPS Action Plan. It also provides links to regulations and information on ongoing legislative and administrative initiatives, among other relevant information.

We consider that the information from “BEPS Monitoring” is useful for tax administrations or policy makers to evaluate the progress of their peers and learn from their experiences, prior to its adoption. This is done with the aim of replicating good practices at the policy or administrative level, which will facilitate the adaptation of measures to the context of developing countries. In addition, the information can be used to support proposals, especially in cases where a greater effort is required to raise awareness among authorities and the society in general. Another potential use for tax administrations is to know the tax rules of various countries to assess the tax consequences of cross-border transactions. This information is also relevant in the academic field.

Currently, the updated “BEPS Monitoring” is published through CIATData[4] as of May 2021. That is why we consider it appropriate to disseminate at this time the main findings that we have identified for a selection of the 29 countries from the Latin American and Caribbean region.

The first of them is related to the title of this post, and it is precisely related with the political will to prevent and combat the tax base erosion and the shifting of profits demonstrated by a significant portion of countries in the region. For example, of the 29 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean that have been selected, 69 per cent (20 countries) are part of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS (IF on BEPS). This shows that there is a commitment to devote efforts to various working groups and to implement a minimum standard consisting of four actions (Actions 5, 6, 13 and 14). In addition, several countries have voluntarily implemented recommendations for measures of the BEPS Action Plan for which there is not yet a need to assume commitments within the OECD. The latter demonstrates the desirability of these recommendations for a significant group of countries and confirms their interest in addressing this problem.

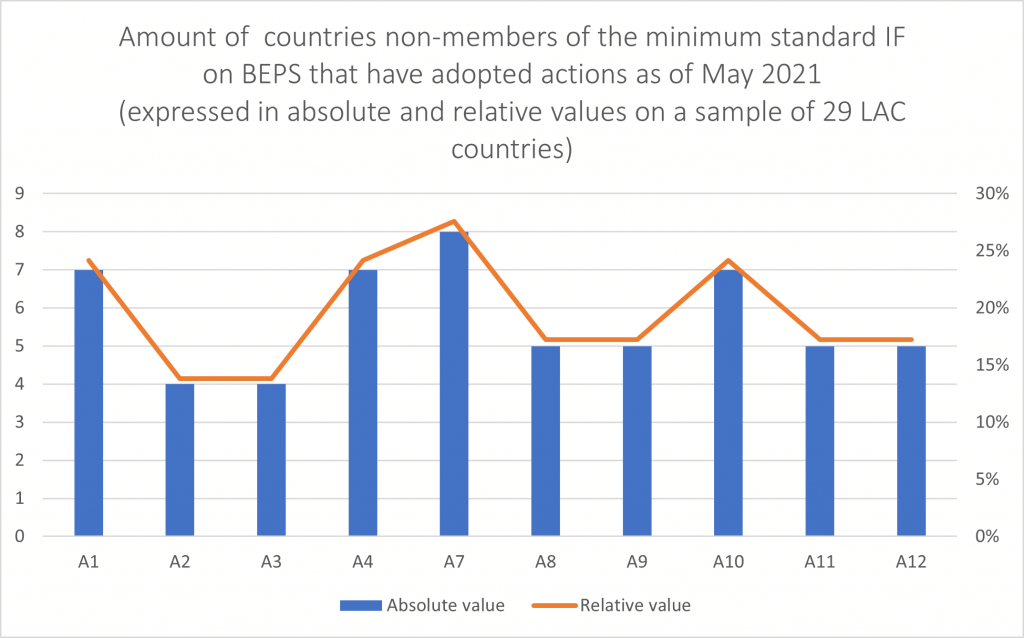

The following graph shows the number of countries that adopted actions that are not part of the BEPS IF (Action 15 is excluded, as it is a tool for implementing other actions that are mainly part of the IF on BEPS minimum standard).

Figure 1. Number of countries having adopted actions that are not part of the minimum standard of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS, as of May 2021. The blue bars represent the number of countries that adopted these actions, expressed in absolute values and the orange bars represent the same information in relative values, considering the sample of 29 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

The percentage of countries in the sample that adopted actions that are not part of the IF on BEPS minimum standard may seem low. However, it should be considered that the voluntary adoption of these actions is mainly concentrated in Latin American countries (16 of the 29 countries in the sample). In this sense, the impact of BEPS in this subregion of the Americas is significantly greater than its impact in the Caribbean countries. Perhaps one element that justifies this is the greater development of tax administrations in Latin America and the expected relevance of the impact of some specific actions in the context of countries larger than those that are part of the Caribbean subregion. Of the Latin American countries, some that are not yet part of the IF on BEPS have adopted its recommendations, including Ecuador (A1, A4, A5, A6, A8-10, A12), which has taken significant steps, and Salvador (A14).

Actions related to the taxation of the digital economy (A1), limiting the erosion of the tax base through interest deductions and other financial payments (A4), mechanisms to prevent artificial avoidance of permanent establishment status (A7), and the need to ensure that transfer pricing results are in line with value creation, in particular in relation to other high-risk operations (A10) were implemented in whole or in part by more than 31% of the countries in the sample. Regarding the A1, several of the countries analyzed focused on the implementation of mechanisms related to the taxation of indirect taxes, mainly through means of payment and to a lesser extent through registration, declaration and payment systems, for taxpayers who operate without a physical presence in the country. We hope that the adoption of registration, declaration and payment systems, inspired by the recommendations of the OECD guidelines on indirect taxation and the digital economy will grow as a result of the impetus of the CIAT-NORAD (Norwegian Cooperation) initiative called DEC (Digital Economy Compliance), which makes available to the tax administrations a configurable software that facilitates the management of tax obligations for this type of subjects.

Other actions were taken by a smaller group of countries, with Action 2, which aims to neutralize the effects of hybrid mechanisms, having a lower adoption level than other actions. It is also worth noting that, despite the fact that the recommendations in the field of transfer pricing have substantive improvements in regard to the current system, and that the control of transfer pricing is one of the most relevant issues of the international taxation for the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean over the last few decades, there is a low relative level of adoption of actions 8 (5 countries) and 9 (5 countries).

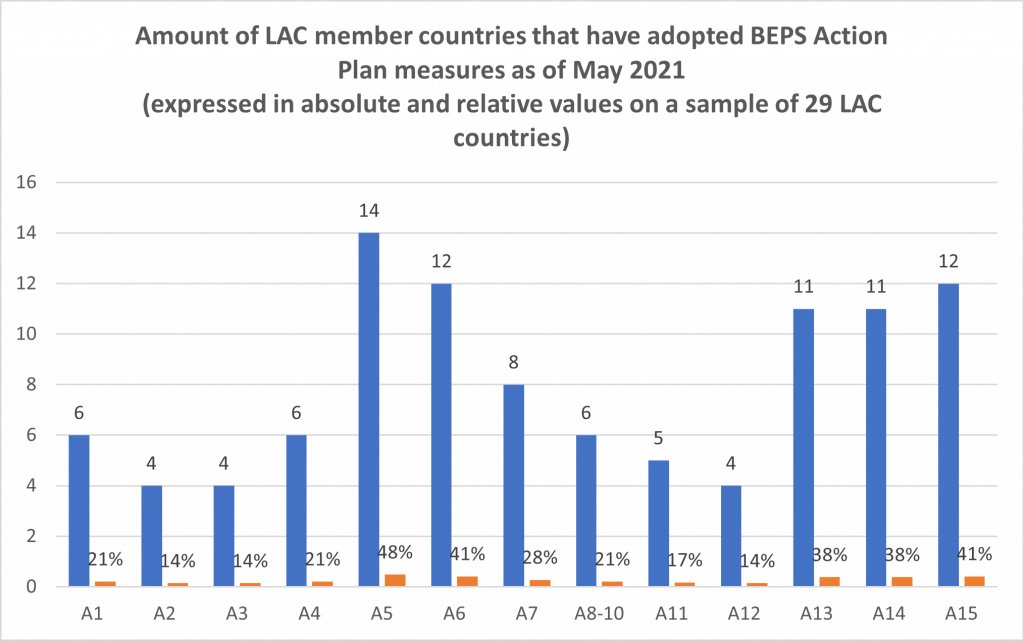

The four actions that are part of the minimum standard of the IF on BEPS have logically had a higher level of adoption among the countries that are part of the IF on BEPS. The impact is similar in relation to the adoption of Action 15, as this is a tool to implement much of the recommendations of the minimum standard.

Figure 2. Number of LAC member countries (from the sample of 29) that implemented BEPS Action Plan measures as of May 2021. The blue bars represent the number of countries that implemented these actions in absolute values and the orange bars represent the same information in relative values, considering the total number of LAC countries in the sample.

In line with the comment made earlier on the interest of countries in the field of transfer pricing control, it is worth highlighting that the adoption of Action 13 (transfer pricing documentation) has had a slightly lower impact than other actions that are part of the minimum standard of the IF on BEPS (A5 and A6).

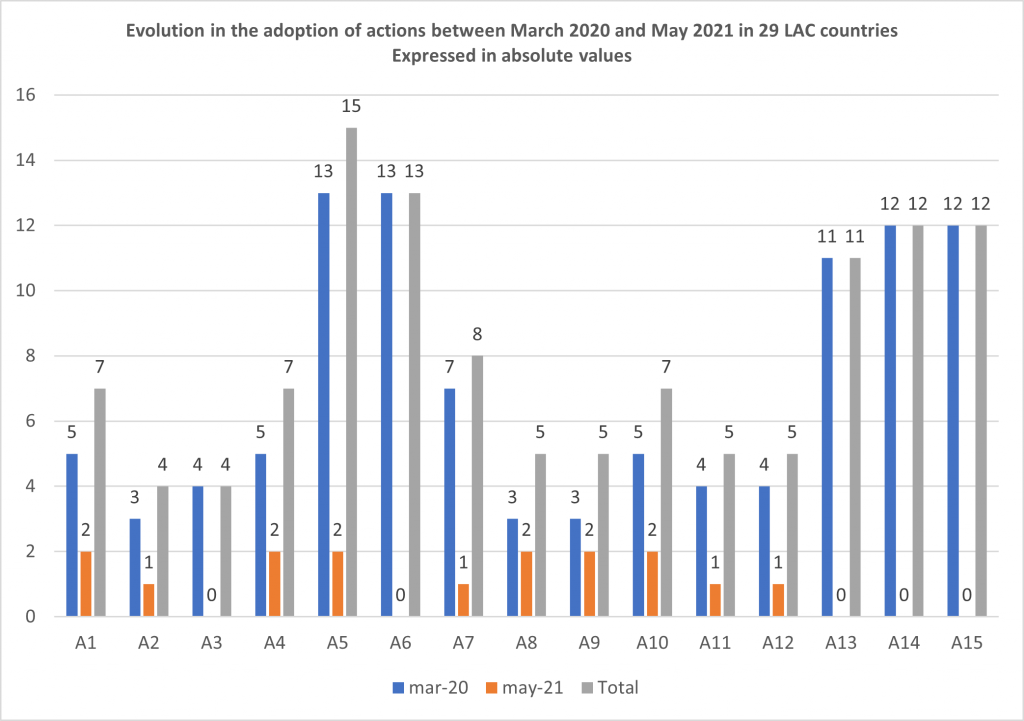

Between March 2020 (the date that coincides with the beginning of the pandemic in the region) and May 2021, there has been a non-significant increase in the adoption of BEPS actions in the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, with the most impact in actions 1, 4, 5, 8, 9 and 10 (between 1 and 2 countries, depending on the action). For its part, the level of implementation of actions 3, 6, 13, 14 and 15 has not changed in the aforementioned period, despite actions 6, 13 and 14 being part of the minimum standard of the BEPS IF. The following graph shows a detail of the comments.

Figure 3. Evolution in the adoption of actions between March 2020 and May 2021 in 29 LAC countries. The blue bars show the number of countries that adopted actions before March 2020, the orange bars show the number of countries that have adopted actions between March 2020 and May 2021 and the grey bars show the total actions adopted, as of May 2021.

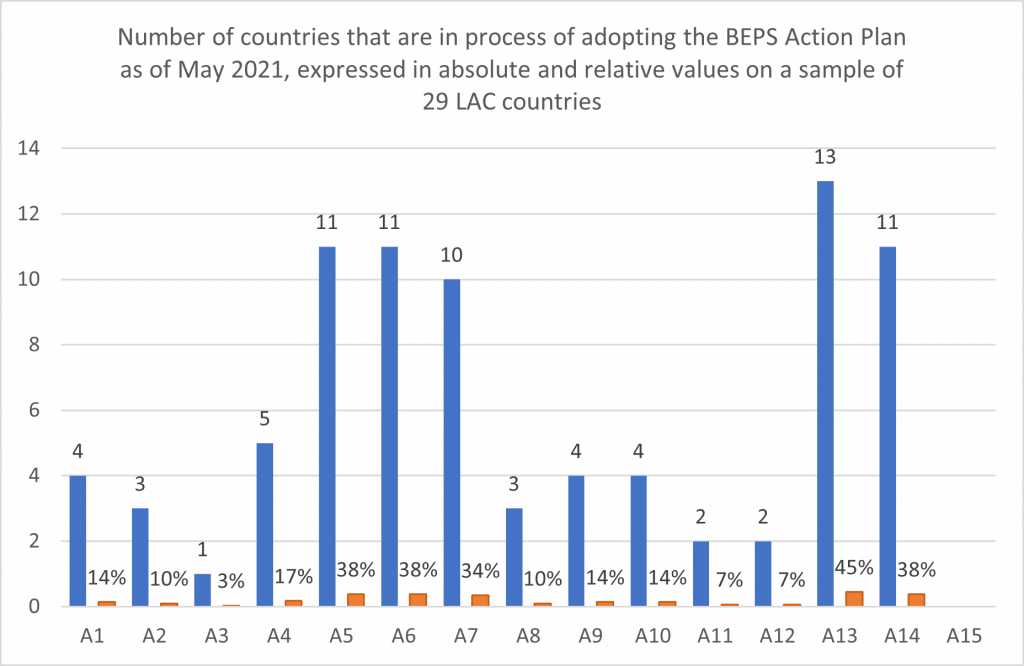

Despite the small increase in the adoption of measures between March 2020 and May 2021, the outlook for the future is optimistic. Several countries are working on the formulation of legal and/or administrative norms to implement more recommendations from actions already adopted or to implement new action points. Even non-members of the BEPS Inclusive Framework believe in the implementation of certain BEPS measures. For example, Ecuador is working on expanding Action 12, El Salvador plans to incorporate actions 1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 13, while Guatemala plans to incorporate action 10. The following graph provides information about this.

Figure 4. Number of countries that are in the process of adopting measures from the BEPS Action Plan in 29 LAC countries, as of May 2021.

The recommendations of the BEPS Action Plan are an opportunity for the LAC countries to have the technical and political support that will allow them to provide greater substance, coherence and transparency to their domestic and international tax systems, especially with regard to tax compliance by multinational companies. While the countries of the region have progressed a lot, there is still a long way to go and many lessons to be learned, which will be glimpsed as it becomes possible to calculate the impact of these measures for each of the countries that effectively implemented them. We also expect the BEPS Action Plan to evolve as a result of feedback once the recommendations are consistently implemented. In this regard, it should be noted that progress is a constant need, which is why the rules must be “written in pencil” so that they are easily adaptable to the needs imposed by the dynamic context that countries face. To do this, it will be necessary to monitor the progress that is being generated and, in some years, to look through the rear-view mirror to analyze the correlation between the adoption of the BEPS recommendations and the capacity of countries to mobilize domestic resources aimed at the sustainable development of societies.

We take the opportunity to thank the collaboration of those tax administrations that provided information to make it possible to update the “BEPS Monitoring” database and invite them to consult this resource in CIATData.

[1] The plan consists of 15 actions to combat base erosion and profit shifting (‘BEPS’) which were developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

[2] When we refer to the adoption of BEPS measures, we rely on the information provided by the sample countries and do not necessarily ensure that such adoption meets the criteria that the OECD would use in peer reviews.

[3] We understand by “partial adoption”, the adoption of part of the recommended measures in each action that integrates the BEPS Action Plan. We are not referring to the adoption of measures partially inspired by those recommendations.

[4] The table ‘Date of Update’ shows the dates on which the updated information was received from each country.

3,904 total views, 1 views today