The COP 28 and the Climate Change performance index in 2024

“Alice laughed: “There’s no use trying,” she said; “one can’t believe impossible things.” “I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was younger, I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.” (Lewis Caroll, Alice in Wonderland)

As you may know, the 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference or Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, more commonly known as COP28, was the 28th United Nations Climate Change conference, held from 30 November to 13 December at Expo City, Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

It was the first time that the COP explicitly addressed the need to end the use of coal, oil and gas, the main drivers of the climate crisis. The agreement also calls for tripling renewable energy capacity worldwide by 2030 and accelerating technologies such as carbon capture and storage. The final compromise agreement between the countries involved had been reached on December 13, 2023. The agreement commits all signatory countries to move away from carbon energy sources “in a just, orderly and equitable manner” to mitigate the worst effects of climate change, and reach net zero emissions by 2050. This terminology avoided calling for a fossil fuel phaseout, as requested by the two-year assessment of global progress in slowing down climate change, called the “global stocktake“. It was subsequently rejected by the Umbrella Group (Non-EU developed countries) and the Alliance of Small Island States, which described the draft as a “death certificate” for small island nations. However, the mention of fossil fuels as driver of the climate crisis is explicit for the first time in the COP history.

The most successful declaration of the summit, in term of number of countries joining, was the COP 28 Declaration on sustainable agriculture, resilient food systems and climate action[1]. It was signed by 159 countries (Out of a total of 198 parties, i.e., 197 countries plus the European Union)

Financing the losses and damages

In our last blog, I presented the financial instrument for financing the losses and damages of the climate crisis. On the starting day of the summit on 30 November 2023, a “loss and damage” fund to compensate poor states for the effects of climate change was agreed on. The fund aims to distribute funds to poor states harmed by climate change and is to be administered by the World Bank. Initial promises were made by the host (UAE) to donate $100 million to the fund, and by the United Kingdom ($75 million), United States ($24.5 million), Japan ($10 million) and Germany ($100 million). In the future, a mechanism of financing more efficient than voluntary donation will be needed.

The head of the International Monetary Fund, Kristalina Georgieva, expressed satisfaction from the beginning of the conference because the loss and damage fund were created, but said that for further decarbonization, carbon pricing should be advanced and fossil fuel subsidies should be eliminated.

Net zero emissions and carbon sequestration

Global net zero emissions describe the state where emissions of carbon dioxide due to human activities and removals of these gases are in balance over a given period. It is often called simply net zero. In the last few years, net zero has become the main framework for climate ambition. Both countries and organizations are setting net zero targets. Today more than 140 countries have a net zero emissions target. They include some countries that were resistant to climate action in previous decades.

However, to prevent a catastrophic acceleration of climate disasters, a future net zero goal is not ambitious enough. It is necessary to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (CDR, carbon dioxide removal), through natural or technological system. Examples of CDR include planting trees on previously deforested or unforested lands, producing bio-energy and capturing and storing the emitted carbon, fertilizing the ocean to stimulate biological production and capturing CO₂ directly from the air through chemical and technological means. The goal is to restore the atmosphere to a level of CO2 considered as safe for the climate, which means under 350 parts per million of particles in the atmosphere. This approach calls for policies of both carbon fee and dividends, and carbon sequestration.

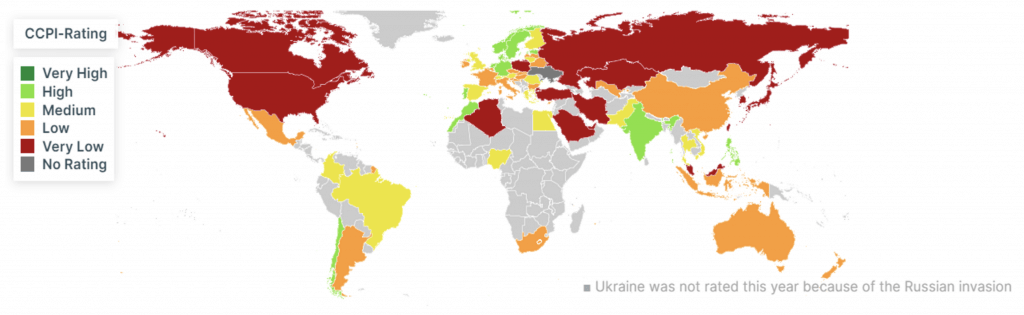

The Climate change performance index

The Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) is a scoring system designed by the German environmental and development organization Germanwatch e.V. to enhance transparency in international climate politics. On the basis of standardized criteria, the index evaluates and compares the climate protection performance of 63 countries and the European Union (EU) (status CCPI 2022), which are together responsible for more than 90% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The climate protection performance is assessed in four categories: GHG Emissions, Renewable Energy, Energy Use and Climate Policy.

According to these categories, the best performers are not centered in the developed world, which seems to be a more balanced outcome than the single carbon pricing criterion.

Source: CCPI[2]

Here, the Philippines, India and Morocco appear in the top seven countries, since the three first places are empty: No country is considered performing sufficiently well to occupy the top three positions in the index. This year, Denmark, reaches the positions 4. “Danish climate action has nearly paused since October 2022, when national elections were called. Before that time, many of the sectoral climate agreements, such as the legally binding economy-wide target of a 70% reduction in 2030 and net zero in 2045–2050, were to be strengthened in 2023. Number 5 and 6 are Estonia and the Philippines.

These are followed by India (7), the Netherlands (8), Morocco (9) and Sweden (10). “India receives a high ranking in the GHG Emissions and Energy Use categories, but a medium in Climate Policy and Renewable Energy, as in the previous year. While India is the world’s most populous country, it has relatively low per capita emissions. In the per capita GHG category, the country is on track to meet a benchmark of well below 2°C.”

The first Latin American country is Chile, the only one considered as high performing, in position 11 on the index. We can read in the report that “Chile receives a high rating in the GHG Emissions category, medium in Climate Policy and Renewable Energy, and low in Energy Use, due to the country’s unambitious target and weak showing in GHG per capita compared with a well-below-2°C benchmark.

For its part, “Brazil is recovering the position 23, since the country in 2023 has restricted deforestation, promoted the expansion of renewable energy and returned to its original NDC” (Nationally Determined Contribution)

Taxation and sustainability: Carbon pricing stagnation

Regarding taxation, the role of the national tax systems in the sustainability of national policies is recognized, but still rarely studied. the sustainable tax system as a “tax system that contributes to the sustainability of a country’s basic pillars in order to meet the needs of the present generation without putting limitations on future ones.” In fact, 2023 and probably 2024 are announced as years of stagnation for the pricing of carbon emissions[3]. There is a crisis of confidence with the market of carbon credits. Fortunately, the price of renewable energies keeps going down, and we can hope that this crisis will bring more transparency and efficiency in these markets.

Fortunately, the price of renewables continues to decrease, and we can expect this crisis to bring more transparency and efficiency to these markets. In a future blog, we will talk more about this temporary stagnation of the carbon pricing, which is also related to the increase in conflicts and the high instability of international relations.

Tentative conclusion

There is a huge gap between the ambitious global declarations of intention, as shown by COP 28, and the political will at national levels, and international conflicts often prevent from leading long-term policies. This year, in many countries, there are possible governments changes towards parties that consider strong climate action and existing multilateral treaties in general as threats rather than opportunities. It is common sense to say that the global threats require multilateral action. Let us hope that common sense will prevail this year.

[1]https://www.cop28.com/en/food-and-agriculture

[3] https://carboncredits.com/carbon-prices-and-voluntary-carbon-markets-faced-major-declines-in-2023-whats-next-for-2024/

26,383 total views, 17 views today