Climate-related public tax policies in 2023 (Latin America) -Part 2

After presenting the guidelines of climate policies in the G-7 countries, we dedicate this second part [1] to the policy instruments of developing countries, particularly Latin America.

In developing countries, the landscape of tax measures related to climate change is changing rapidly, however, if states take urgent and specific measures to face environmental and climate challenges, state-level policies often lack multilateral coordination: There is often a competition between short-term energy investments and national policies with environmental policy frameworks of energy transition and biodiversity preservation.

Multilateral financial organizations, MDB, IMF, World Bank, IDB, keep taking new measures to link financing and investments to developing countries with the implementation of measures to limit carbon emissions and preserve biodiversity. [2] On the other hand, the high prices of fossil energies continue to invite maintaining or increasing production in the countries that export them. More internal coordination of each state is needed to avoid clashes of priorities in development financing policies, especially since, as a result of the global COVID pandemic, the climate crisis affecting agriculture, and wars, extreme poverty has increased in recent years.

At the tax level, in some aspects the TA databases should be updated to integrate potential climate change data: If a region of a state suffers from an acute drought or a more intense period of floods than in the past, the programs should be able to anticipate these situations, facilitate the temporary reduction or suspension of taxes of the affected areas, for example real estate taxes and/or the agricultural sector. It is not desirable to wait for situations of total tragedy such as the floods in Pakistan in 2022, in order to integrate the dimension of the climate emergency into the state financial planning.

Latin America

A recent study by the Thomson Reuters Foundation analyzes and compares the environmental frameworks related to climate change in Latin America.

“Latin America is expected to be one of the regions of the world where the effects and impacts of climate change will be most intense.”

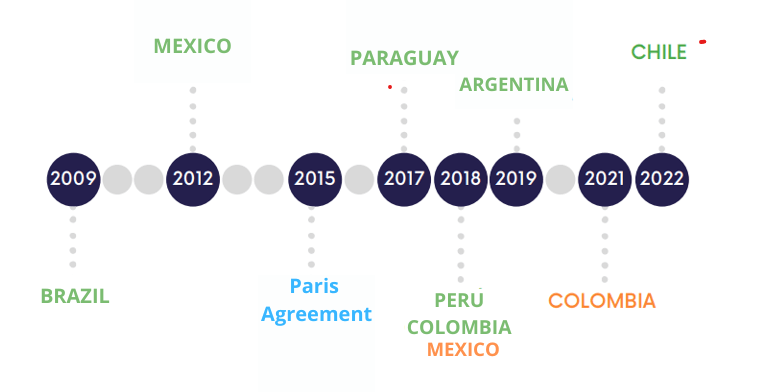

All the countries of the region have ratified the Paris Agreement (PA) and submitted their respective NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions). However, only 7 countries have a climate change framework law (CCFL) in LAC. A CCFL law, as defined by the International Energy Agency, establishes the principles and main aspects of climate change policy. Its objective is to coordinate and support the comprehensive management, in a participatory and transparent way, of climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, complying with the international commitments of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and contributing to low-carbon development opportunities. The introduction of climate policy in the framework law helps to reduce the possibility of setbacks in this area and provides a mandate to policy makers to move forward with coordinated action.

Source: Climate Change Legislation Report, Thomson Reuters Foundation.

With regard to the seven countries mentioned in the graph, which already have their CCFL, they must continue to promote more ambitious initiatives and in line with the reality that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change points out to us more starkly year after year. [3] The existence of a CCFL allows for more coherence in national policies. Brazil was the first LAC country that had adopted a framework law on climate change, in 2009.

Some countries such as Ecuador, despite not appearing on this list, have key articles on environmental policy in their political constitution, which could easily be translated into an CCFL. Others, like Uruguay or Costa Rica, have also developed an ambitious environmental and climate policy.

C-PIMA: Evaluation tool

The IMF has developed a tool for the Evaluation of public investment management in relation to climate (C-PIMA, Climate-Public Investment Management Assessment) [4]. C-PIMA involves an evaluation of the five public investment management institutions that are key to a climate-friendly infrastructure: C1. Climate-friendly planning. C2 Coordination between entities. C3 Evaluation and selection of projects. C4 Budgeting and portfolio management. C5 Risk management Each institution is further analyzed according to three dimensions that reflect the key characteristics of the institution.

Tax administrations are not directly responsible for a country’s public investment, but they must include climate-related risks among their projections.

A beneficial investment trend for international trade is the “Nearshoring” [5], which, unlike “offshoring”, consists, for multinational groups, in favoring production in countries close to the main consumer markets of the products, avoiding the costs of emissions and environmental cost associated with long transports. In AL, Mexico and Colombia benefit from this trend. [6]

The pricing of carbon emissions in developing countries

A progressive source of income in many developing countries [7]

In the absence of effective global cooperation, developing countries need to take a serious look at carbon pricing and, in particular, carbon taxes. These measures can prevent individuals and companies from making investments in technologies that are then wasted. For example, power companies may invest in new power plants that use high-carbon technologies, but later they will have to discard them, wasting the investment. A real carbon price today provides a strong signal that should help avoid these “lock-in” effects. A second aspect is the importance of sending the message that the authorities are taking climate change seriously.

As a measure of public will to tackle the climate crisis, carbon taxes offer a potentially significant and administratively viable source of revenue. Increasing tax revenues is an important part of the development agendas, and the COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated this need while increasing concern about the sustainability of public finances in some countries. Applying carbon prices in the form of taxes on fossil fuels – as it is done in Colombia, Chile and Mexico- is feasible in most countries, since these goods are usually already taxed (or subsidized) to some extent. In contexts where the informal economy accounts for a large part of economic activity, carbon taxes can be less costly administratively than other types of taxes and offer a way to reduce the fiscal gap between the formal and informal sectors.

Some country data:

- Brazil:

In December 2022, the World Bank announced the Brazil Climate Finance project (Brazil Climate Finance.[8]) The Brazilian Climate Finance Project is a financial intermediation project that aims to encourage companies to reduce their carbon footprint. To this end, the project adopts an innovative results-based financing approach that encourages companies to adopt and implement significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction plans. The project would also increase the access of these companies to high-quality carbon markets. The project proposes to leverage private financing to increase the impact in support of the Brazilian net zero emissions target, including the agricultural and terrestrial sectors. Brazil’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions profile is dominated by agriculture, forestry and land use (AFOLU). In collaboration with Banco do Brasil, the largest bank in Brazil and the market leader in loans to agriculture and land-use-based sectors, the project aims to leverage 1,400 million dollars in private capital and additional CO2 emission reductions by 2030 in a number of sectors, mainly AFOLU sectors.

- Mexico:

At the beginning of February 2023, Mexico has inaugurated the largest solar project in Latin America, in the state of Sonora and welcomes the investment of all countries in its clean energy projects, its foreign minister said on Thursday, launching a diplomatic offensive amid international concern over controversial energy reforms that increase the role of the state in energy production, which according to its detractors favors fossil fuels. [9]

- Colombia:

A comprehensive Tax Reform Law will be applied from January 1, 2023.

This reform expands the scope of the carbon tax to include the sale, self-consumption and import of coal (certain exemptions will apply, including coal intended for export). The rates will increase while remaining specific values per ton, gallon or cubic square. It takes a phased approach to the increase in coal rates from 2023 to 2027. The carbon tax will be deductible for Corporate Income Tax (CIT) purposes. [10]

In conclusion, at COP26, held in Glasgow in 2021, countries agreed to progressively reduce the use of coal, the most polluting fossil fuel. India’s proposal at COP27 to extend this commitment to all fossil fuels won the support of more than 80 governments, including those of the EU, but was opposed by Saudi Arabia and other oil and gas-rich countries.

The final agreement of COP27 in 2022 repeated the commitment to progressively reduce coal-fired energy but did not mention oil and gas.

There are concerns about the possibility of a similar dynamic occurring this year at COP28, which will be held in the United Arab Emirates, the OPEC oil producing country. According to UN scientists, the world must substantially reduce the use of fossil fuels in this decade to avoid the most devastating effects of climate change.

The EU also plans to update its 2030 emissions reduction target under the Paris climate agreement, and set a new one by 2040, in order to guide countries towards the goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050.

[1] See: https://www.ciat.org/ciatblog-repaso-de-politicas-climaticas-con-aspectos-tributarios-para-2023-primera-parte/

[2] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/statement/2023/01/13/world-bank-group-statement-on-evolution-roadmap

[3] https://prensariotila.com/informe-sobre-la-legislacion-de-cambio-climatica-en-latinoamerica/ With link to the study

[4] https://infrastructuregovern.imf.org/content/PIMA/Home/PimaTool/C-PIMA.html

[5] https://www.nextu.com/blog/que-es-el-nearshoring-y-por-que-es-importante-para-america-latina-rc22/

[6] https://www.bizlatinhub.com/es/nearshoring-en-colombia-inversion/

[7] https://ifs.org.uk/articles/what-case-carbon-taxes-developing-countries

[8] https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099800011302228261/p1788880aa8da5060b6c205df5e2d32150

[9] https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230203-mexico-invites-foreign-investment-in-clean-energy-transition

[10] https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-63521117

5,348 total views, 2 views today

1 comment

Amazing Website, I hadn’t noticed ciat.org in advance of my searches!

Look after the vast work!