Tax Amnesty: the tension between cost and benefit

From the axiology of the tax systems, it follows that any non-compliance “per se” is reprehensible and that for this reason the non-compliant must bear financial surcharges and be sanctioned, while from the axiology of tax amnesties[1] it follows that the non-compliant with the highest contributory capacity especially benefit from them. This contradiction of values within taxation creates tension for the tax policy makers.

Their detractors maintain that they favor the non-compliant and therefore demotivates the compliant by damaging tax morality, arguing that any amnesty is counterproductive[2]. Along the same lines, Mexico[3] in 2019 and until 2024, decided not to grant more total or partial amnesties, both for the payment of taxes and their accessories. This measure was preceded by the presidential announcement that in the last 12 years (2007/2018), 153,000 taxpayers had been granted remissions in this way, for 400,902 million pesos (approx. To USD 21,000 million). The main motivation, in the Mexican case, is that most of these remissions had benefited few taxpayers with a high taxable capacity[4].

The resulting question would be: why do countries grant tax amnesties despite the cost of credibility in the tax system that they entail?

Their issuance gives us the answer, depending on the cause that motivated it, namely:

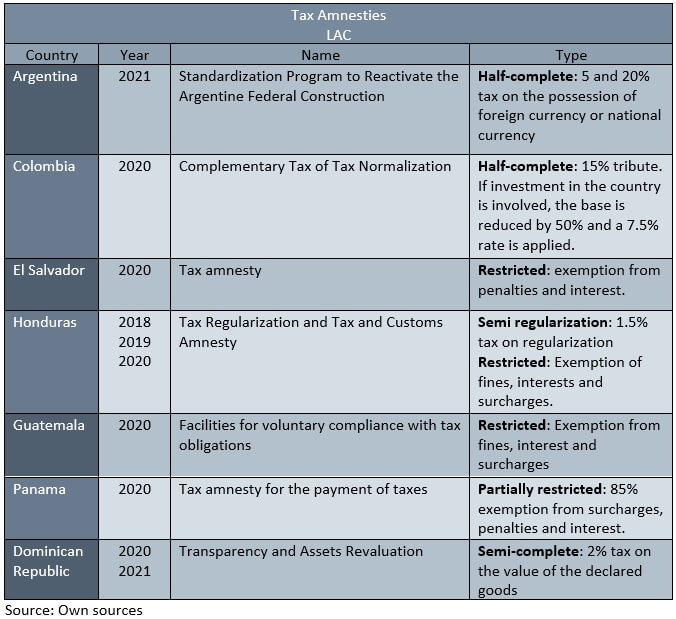

In turn, it is necessary to distinguish that there are different kinds of amnesties according to their depth: 1) Complete: there is tax forgiveness of taxes without consideration requested from the taxpayers, 2) semi-complete: there is tax forgiveness, but with the obligation to pay “the normalization tax”, and 3) restricted: there is no tax release, but there is an exemption from surcharges, interest, and penalties.

In this post we will focus on the analysis of normalizations motivated by tax causes. The first category seeks to obtain immediate income the face of economic distortions, such as the benefits to balance the budget, solve exceptional expenses, favor investments, repatriate goods from abroad, etc. This regulation is considered successful when the income, the growth of tax bases, or the investments made are significant.

With respect to the second category, that is, the normalization of tax obligations whose essential objective is to increase the tax base and improve collection in the next fiscal years, its promoters argue that the cost in the initial credibility that they entailed corresponds to counterbalance the benefit of the important income of the future.

In this regard, the research by Reyes Tagle – Ospina (BID 2020) is interesting[6], where they analyzed the regularizations that were dictated by five countries over time (Argentina, Brazil, Spain, Indonesia, and Italy) since 1991, where it is observed in general lines that the multiple regulations issued did not improve income in the years following their respective issuance[7].

Where this effect is important, it is in the taxation of assets, since the externalization of assets broadens its base and its positive effects are transferred to the next fiscal years[8], which unfortunately can be of little use in Latin America since there are few countries that apply a general assets tax at the national or federal level[9].

Given the economic contraction caused by the coronavirus pandemic, according to ECLAC (2021)[10], tax revenues in LAC fell by 0.5% of GDP in 2020, and those sectorized decreased by 0.3% in Central America, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic, and 0.9% in South America.

Against this background, some countries have introduced tax normalization measures to raise additional revenue, namely:

From the foregoing it follows:

[1]They have received different names depending on the country, namely: forgiveness, moratorium, laundering, normalization, regularization, transparency, externalization, facilities, revaluation, etc. Their essence is that they tend to normalize unfulfilled tax obligations, and they vary according to their scope: i) taxes, accessories (surcharges and interest), and fines, or ii) only accessories (surcharge and interest) and fines.

[2]Jesús Gascón Catalán, General Director of the Spanish Tax Agency: “Any tax amnesty is counterproductive” “… they can provide you with resources at a certain time, but in the medium-term, you are pissing off the general group of taxpayers and those who have doubts about whether meeting or not meeting the expectations ”, El País, 09/12/2020. In the same way, BAER and LE BORGNE (2008) “Tax Amnesties, Theorry, Trends and Some Alternatives”, International Monetary Fund, argue: “International experience, however, shows that the costs of tax amnesty programs often exceed the “benefits” programs.

[3]The Decrees and Provisions that by virtue of Art. 39 of the Fiscal Code of the Federation were repealed, making it possible to grant tax condonations and the measure was adopted of not granting more total or partial condonations on the payment of contributions and their accessories to large taxpayers and tax debtors, with the exception of some extraordinary cases, such as the natural disasters.

[4]54% of that amount was forgiven to only 108 large taxpayers. “AMLO signs the Decree that puts an end to tax remissions”, Expansión, 05/29/2019.

[5]González, Darío “The normalization of tax obligations: tax amnesty”. Tax Administration Review CIAT / AEAT / IEF, Number 11, Panama, 1992.

[6]Reyes Tagle – Ospina “Tax Amnesties in times of Covid: Exceptional measures in exceptional times”. IDB blog. October 2020.

[7]Up to two countries on the list had to issue tax amnesties in two consecutive years.

[8]See the increase in the collection of the Personal Property Tax in Argentina after the 2016 amnesty.

[9]Argentina, Colombia, Uruguay. Venezuela must be included with the Tax on Large Assets and Bolivia with the Tax on Large Fortunes (2021) because it is permanent. The Solidarity Contribution for the Great Fortunes (2021) of Argentina, being for the only time, it is not appropriate to consider it.

[10]ECLAC “Fiscal Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2021”, “Fiscal policy challenges for transformative recovery post-COVID-19”, Santiago, 2021.

4,454 total views, 7 views today