Digital Services Tax (DST): Alive and well

The taxation of cross-border digital services of large global technology corporations in the jurisdictions where they are used constitutes a major concern for the tax policy makers of the LAC countries.

Especially in the context of a digital economy that is equivalent to 15.5% of world GDP and is growing two and a half times faster than global GDP in the last 15 years[1].

Unilateralism or Multilateralism

The tax response to this situation can be multilateral or unilateral. The first is aimed at mitigating double taxation and avoiding a damaging fiscal and trade war between countries. However, given its delay or failure, the objective of the unilateral response is for countries to use their tax sovereignty to obtain fiscal resources from economic acts or events occurring in their countries.

The multilateral response within the framework of the OECD had two axes. The first was the introduction of the concept of the digital permanent establishment to tax such activities with Income Tax in the market jurisdictions, but in the absence of consent for its implementation, the second axis was the proposal of Pillar One, to reallocate a certain part of the taxable profits obtained by large technological multinationals to the jurisdictions where such services are provided.

The delay in its implementation has been due to the complexity of the technical design and the difficulty in obtaining the necessary consensus for its implementation, which has been demonstrated by the need to issue a new “Pillar One Progress Report” to present a complete preliminary version of the technical standards model to apply a new taxation power.

Once the public consultation and its subsequent analysis have been completed, the Inclusive Framework aims to conclude a new Multilateral Agreement, this time scheduled for mid-2023, with the aim of bringing it into force in 2024.

According to the TAX FOUNDATION, in order to achieve the application of Pillar One, the tax technique should be attractive for governments to adopt and simple enough for tax administrations to manage it and for companies to apply it. Although according to his report, the current rules point towards bureaucracy and complexity instead of the simplicity and transparency expected[2].

It argues that it will become mandatory “only after ratification by a critical mass of countries, which will include the jurisdictions of residence of the parent entities of a substantial majority of the companies included in the scope” so the ratification of the United States is necessary for the “substantial majority” to be fulfilled, which requires in that country a two-thirds majority in the Senate, a result that appears according to Bunn and Enache (2022)[3] as extremely unlikely under the current circumstances.

Faced with the indicated delays, the reactions of the states were not long in coming, and many of them proceeded to the application of a Tax on Digital Services (ISD).

This measure[4] tends to tax the corporate income of technological multinationals, through an indirect tax, which is determined by a percentage on the level of turnover of such companies in the jurisdiction where such income is generated.

Therefore, we are dealing with an DST when the taxable person is a corporation that has a certain threshold of global income and also local income, determining the origin of the tax obligation by perfecting one or a series of taxable events with the scope provided by each local legislation (advertising, commercial platforms, digital interfaces, use of user data, use of social networks, etc.).

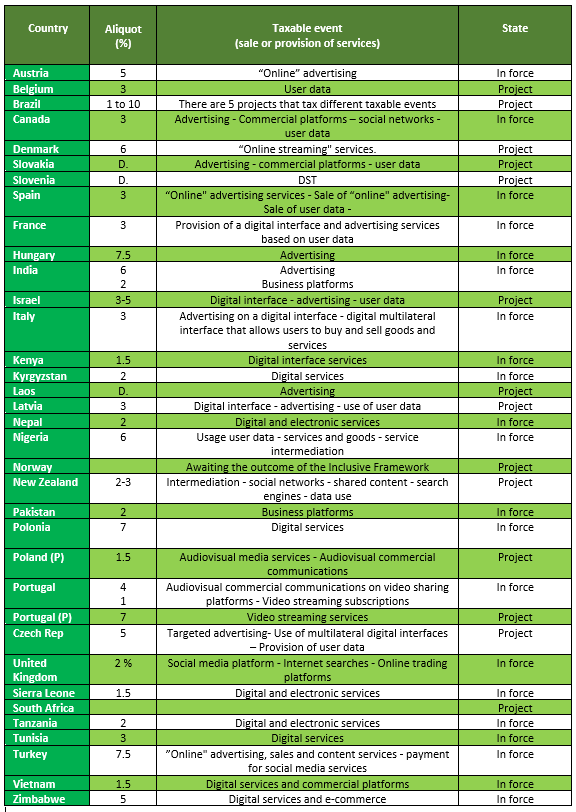

In practice, the level of the aliquot and the taxable events have varied in different countries, as well as the threshold of global and local income to determine the corporation subject to the tax.

Excluded from this tax are the specific tax treatments of the non-resident in the Income Tax, as well as the specific taxes that are applied by the intermediation in travel or lodging, “online” games, etc.

Application

France was the country that led this legitimate option in 2019 by applying the Tax on Digital Services, called in that country “Taxe sur Certains Services Fournis par des Grandes Enterprises du Secteur Numérique[5]”. In turn, the African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF) published in2020 a Model of the DST for its member countries[6]. For its part, the United Nations (UN) added special provisions for revenues from automatized digital services to the Model UN Tax Convention (Article 12B).

The following will describe the main countries where the DST has been proposed or is being implemented:

Fte: Own elaboration based on the data of KPMG, TAX FOUNDATION and VATCalc[7]

While some authors have wondered if the DST was “dead and finished” after the original consensus for the application of Pillar One, by the evolution that events have had to the present, it can be said that it is “alive and well” as reality shows.

Position of the USA.

Since most of the large multinational technological companies have American origin, that country opportunely opposed the application of the DST and announced the application of tariff reprisals to those who implemented it.

But this conflict was resolved on October 21, 2021, by formulating a joint statement among Austria, France, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States, in which a plan was presented to reduce taxes on digital services and retaliatory tariff threats, when the rules of Pillar One are implemented. Turkey later agreed to the same terms.

In it, it was agreed that the DST accrued between January 1, 2022, and the effective date of Pillar One or December 31, 2023, whichever is earlier, will be compared with the amount of the “Pillar One tax”. If that amount of the accumulated DST is greater, in the specific jurisdiction in the first year of validity of Pillar One, the excess amount will be credited to multinational technology companies [8].[9]

However, if the application of Pillar One is finalized, there would be a transition with minimal double taxation for companies that would be subject to both Pillar One and the current taxes on digital services.

Conclusion

The delays or the possible lack of final consensus that prevents the application of Pillar One, has generated an intense tax policy debate in LAC countries, pressed by the need to obtain tax revenues from digital economic activities or events that originate in their territories.

One position is inclined towards the creation of a temporary or definitive DST in their tax systems, in the face of the delay or non-application of Pillar One, following the path traced by many European, Asian, African countries and by Canada on our continent.

On the other hand, BARREIX, PINEDA, FRUTOS, BES and RICCARDI (2022)[10] argue that “it is recommended to weigh the convenience of these countries to participate in Pillar 1, compared to less aligned alternatives, such as the Tax on Digital Services”.

[1] WORLD BANK (2022) Digital Development https://www.bancomundial.org/es/topic/digitaldevelopment/overview

[2] Bunn, Daniel (2022) “Rushing Headlong into Form Application” https://taxfoundation.org/formulary-apportionment-oecd-tax-deal

[3] BUNN, Daniel and Enache, Cristina (2022) “Tax Foundation Response to OECD Consultation on Amount A of Pillar One” https://taxfoundation.org/oecd-pillar-one-amount-a-consultation

[4] Regardless of the name that each country gives it.

[5] Gonzalez, Darío (2020) “Digital Services Tax (Digital Services Tax)” https://www.ciat.org/impuesto-sobre-servicios-digitales-digital-services-tax/

[6] AHANCHIAN, Amie (2021) “Digital Services Tax: Why the world is watching”, Bloomberg Tax. https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report/digital-services-tax-why-the-world-is-watching

[7] ASQUITIH, Richard (2022) “Digital Services Taxes DST”, Global Tracker https://www.vatcalc.com/global/digital-services-taxes-dst-global-tracker/

[8] VRANCKX, Gert, SMET, Rik (2021) “International Tax Update: Digital Service Tax: Dead and done with?”, Tiberghien, https://tiberghien.com/en/3244/digital-service-tax-dead-and-done-with

[9] Corporations that do not meet the thresholds of Pillar One will not have credit to compute.

[10] “Advances and challenges of the new international taxation” (2022) https://blogs.iadb.org/gestion-fiscal/es/avances-y-desafios-de-la-nueva-fiscalidad-internacional-para-america-latina-y-el-caribe/

9,034 total views, 20 views today